Unpredictable Patterns #132: Margaret Boden and creativity

Sketch, draft, iteration, subject, struggle and madness in models of creativity

Dear reader,

This week a note to remember Margaret Boden, focused on one of the questions she was intensely interested in: creativity. This is an issue we will be discussing for a long time - but always against the background of Boden’s work.

Boden’s legacy

This summer saw AI-giant Margaret Boden leave us at 88. Her work cannot be appreciated enough - both the fact that she was early to realize some of the core challenges the technology brings (witness her discussion of the use of computer programs in psychological health contexts in the concluding chapters of Artificial Intelligence and Natural Man (1977)) and the lasting legacy of some of her core research interests as the question about creativity and artificial intelligence show her to have been one of the great pioneers in thinking about AI. I remember reading Artificial Intelligence and Natural Man in university and finding it such a fundamentally humanist approach to the question of AI, as opposed to the many technical discussions I had read previously.

The question of creativity is explored in detail in her 1998 paper on the subject.1 She introduced a distinction between P-creativity and H-creativity that remains useful when discussing the questions around AI and creativity today:

A creative idea is one which is novel, surprising, and valuable (interesting, useful, beautiful. .). But “novel” has two importantly different senses here. The idea may be novel with respect only to the mind of the individual (or AI-system) concerned or, so far as we know, to the whole of previous history. The ability to produce novelties of the former kind may be called P-creativity (P for psychological), the latter H-creativity (H for historical). P-creativity is the more fundamental notion, of which H-creativity is a special case.

She also suggested that we think about creativity as three different processes:

There are three main types of creativity, involving different ways of generating the novel ideas. Each of the three results in surprises, but only one (the third) can lead to the “shock’ of surprise that greets an apparently impossible idea. All types include some H-creative examples, but the creators celebrated in the history books are more often valued for their achievements in respect of the third type of creativity.

The first type involves novel (improbable) combinations of familiar ideas. Let us call this “combinational” creativity. Examples include much poetic imagery, and also analogy-wherein the two newly associated ideas share some inherent conceptual structure. Analogies are sometimes explored and developed at some length, for purposes of rhetoric or problem-solving. But even the mere generation, or appreciation, of an apt analogy involves a (not necessarily conscious) judicious structural mapping, whereby the similarities of structure are not only noticed but are judged in terms of their strength and depth.

The second and third types are closely linked, and more similar to each other than either is to the first. They are “exploratory” and “transformational” creativity. The former involves the generation of novel ideas by the exploration of structured conceptual spaces. This often results in structures (“ideas”) that are not only novel, but unexpected. One can immediately see, however, that they satisfy the canons of the thinking-style concerned. The latter involves the transformation of some (one or more) dimension of the space, so that new structures can be generated which could not have arisen before. The more fundamental the dimension concerned, and the more powerful the transformation, the more surprising the new ideas will be. These two forms of creativity shade into one another, since exploration of the space can include minimal “tweaking” of fairly superficial constraints. The distinction between a tweak and a transform is to some extent a matter of judgement, but the more well-defined the space, the clearer this distinction can be.

Now the best we can do to honor someone who has spent their life blazing a path in a specific subject is to engage with their ideas, so this is what we will do her — and specifically we will speak about the nature of creative iteration and the creative subject.

Outline of a criticism

The models of creativity that Boden presents in her 1998 paper could be criticizes as overly linear, or overly oriented towards the idea as a search in a specific space. This idea, that creativity is a search, has since become so prevalent that it would not be preposterous to argue that it is now the most adopted model of creativity - and it is incredibly powerful. In this model there is a space of solutions to a challenge, problem or even a general idea space, and creativity is the ability to find or combine ideas we have found in the search in different ways.

With the model we can explore how systems create generally: evolution itself is a search process that creates new life forms and adaptations over time, and civilization works the same way. Musical or literary creativity is a search through space for new motifs, metaphors, narratives and characters. This is - in other words - a very powerful and generative model that is incredibly helpful in exploring a lot of different problems.

But that does not mean that we cannot challenge it, so let’s do that and see where we end up. Here is the outline of the challenge I think we should explore:

Boden envisions creativity as a search process.

This process, however, is deeply linear. Even her combinational creativity takes two elements and combines them, and that is the essence of creativity - a step by step process.

Creativity, however, is never linear - it is deeply iterative, and cyclical.

Human artists draft, sketch, and model - in many, many iterations before they settle on a result.

This could be represented as a cyclical search, but that ignores something fundamental: the change in the creative subject brought about by every single iteration.

Creativity then is iterative, and performed by a creative subject that changes with each iteration - the draft and the sketch change the creator.

A corollary to this: creativity never converges on a single point in a space like a search: it keeps shifting and changing.

The true measure of creativity is the difference between iterations.

Therefore a model of creativity that divorces it from the change in the creative subject through iterations will lose something important. This neglects - as we often do in modelling intelligence - the temporal aspect of the phenomena at hand.

You might - should - protest that this simplifies Boden’s model to a point where I am almost arguing against a caricature - but I don’t think that it is true: I think there is a key move in a lot of cognitive science which is to assume that a mental process can be divorced from actor. This methodological move is helpful when thinking about game playing - where the actor does not change with the moves, but it does not work for this other category of processes.

We may even want to think about two kinds of cognition here: one where there is a way for us to linearly search for a solution that can be evaluated against an objective function of some kind, and one where there is a constant iteration against the actor, and the actor serves as the objective function. The first is linear, the other circular and dependent on the development of an equilibrium between the created and the creator.

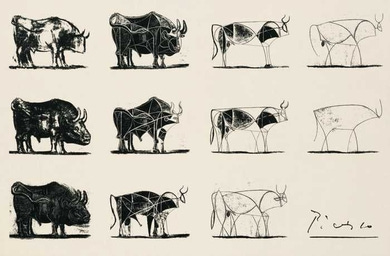

We could still model this as a search, but it is a search for an equilibrium between work and creator. An interesting example of something like this is Picasso’s paintings of a bull (Le Taureau):

Wikipedia quotes his assistant, Fernand Mourlot, as writing “in order to achieve his pure and linear rendering of the bull, he had to pass through all the intermediary stages".”

And Picasso also gives us another example of how the creative subject and iteration connect: his artistry develops over time, a constant iteration between work and creator into styles and periods. These periods and styles are evident everywhere we look at human creativity. Witness the development of Arvo Pärts Tintinnabuli-style music - which he himself comments on:2

Tintinnabulation is an area I sometimes wander into when I am searching for answers – in my life, my music, my work. In my dark hours, I have the certain feeling that everything outside this one thing has no meaning. The complex and many-faceted only confuses me, and I must search for unity. What is it, this one thing, and how do I find my way to it? Traces of this perfect thing appear in many guises – and everything that is unimportant falls away. Tintinnabulation is like this. . . . The three notes of a triad are like bells. And that is why I call it tintinnabulation.

It is a search, you could say - but the subject is front and center: this is not a subject-less search process, but an individual that wanders into a region of music, when he searches for something. An interation driven by the subject himself, changing him and the path.

It is worth noting that Pärt’s style here originated in a creative crisis. This constant need to change oneself is a key element of creativity that often is lost in the models we apply - if we want to make a truly creative AI, then we have to ensure that it can develop styles, have creative crisis and ultimately lapse into years of silence. These are not marginal phenomena in creativity, but at the very heart of what creativity is.

Creativity, struggle, madness

We may sigh and roll our eyes when someone speaks of a creative struggle - but there is a lot of truth to the idea of it: creativity might be best modeled as an on-going negotiation between the work and the author, where the work changes the author as much as the author the work.

This in turn probably tells us something important about the ability humans have to thread our consciousness in different ways - the stories of characters living their own lives, and the author feeling reduced to merely taking notes are stories of an infinitely weirder intelligence than the one we have built so far. This is by no means safe and any model of creativity should also articulate the risks associated with the creative process.

Let’s look at an example: Hölderlin's descent into madness after 1806 presents one of literature's most haunting examples of creativity's potential to unmake its practitioner.3 His late hymns - Patmos, The Rhine, Mnemosyne - written on the precipice of mental collapse, achieve a fragmentary brilliance that seems to emerge precisely from the dissolution of conventional semantic boundaries, as if language itself were breaking apart to reveal some underlying luminous structure.

The thirty-six years he spent in the Tübingen tower, cared for by carpenter Ernst Zimmer, producing simple rhyming verses signed with impossible dates and the name "Scardanelli," suggest not merely a mind destroyed but transformed - the grand mythological architectures of his earlier work replaced by an almost childlike immediacy that paradoxically contains its own profound truth. His famous response to visitors asking for poems - immediately composing verses on demand with mechanical precision - hints at a creativity that had become automatic, unconscious, freed from the self that had originally shaped it.

This transformation terrifies because it suggests creativity might ultimately consume the creator, that the iterative dialogue between artist and work could spiral into a space where the artist dissolves entirely into pure process, leaving behind only the strange, luminous fragments that continue to haunt German literature like messages from an unreachable shore.

The iterative dialogue of creativity unfolds, after all, against the horizon of death.

Was Lady Lovelace right?

Does this mean that a machine cannot be creative?

Lady Lovelace’s challenge to artificial intelligence has become canon today, and artists routinely reject the idea of machine creativity.4 Their basis for doing so is exactly what we have pointed to here - the machine does not struggle, has no crisis, does not change as it writes a tragic novel. When I ask my LLM to write a tragedy, the characters do not dwell with the model late at night asking why they had to suffer so.

But ultimately this too is wrong: we should not try to save creativity from the machine, but rather understand it and take the challenge: why should a machine not be able to truly change as it creates? It requires a different kind of architecture, one in which the weights and parameters are shifted and changed with the work produced, where styles and periods can emerge and where creative crisis is a real probability. Such systems are not impossible, as we are evidence enough to show.

The idea that they cannot be built is defeatist and scoffs at our ingenuity - and our creativity.

Thanks for reading.

Nicklas

See both Boden, M.A., 1998. Creativity and artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence, 103(1-2), pp.347-356 and later works Boden, M.A., 2004. The creative mind: Myths and mechanisms. Routledge and Boden, M.A., 2009. Computer models of creativity. Ai Magazine, 30(3), pp.23-23.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tintinnabuli

Current day diagnosis is always a fraught thing - some argue that he suffered from shizophrenia.

Nick Cave’s famous diatribe is worth reading here: https://www.theredhandfiles.com/chat-gpt-what-do-you-think/

Deeply saddened to read about Margaret Boden’s passing. She was a titan, and Mind as Machine remains the best AI history book around. Thanks very much for writing this.

Hi Nicklas, I was wondering if you would be interested in participating in our research about the future of AI in Creative Industries? Would be really keen to hear your perspectives. It only takes 10mins and I am sure you will find it interesting.

https://form.typeform.com/to/EZlPfCGm