Unpredictable Patterns #126: The NatSec Shift

What is your p(trigger)?

Dear reader,

This week’s note is about what happens when a technology becomes so powerful as to make the free market institutional framework seem less able to regulate it - and how the state might then react - and what the probability of that is. Let me know what your p(trigger) is!

TL;DR

As AI capabilities accelerate, corporations are hedging against a potential government takeover ("the shift") by announcing infrastructure investments and pursuing defense contracts. While the probability of triggering events (breakthrough discoveries, demonstrated threats, corporate misbehavior) remains uncertain, the existential cost of exclusion from any future government-led consortium makes hedging rational even at low probabilities. Civil society should proactively develop oversight frameworks now, before any crisis forces hasty decisions.

The shift

It has probably not escaped anyone’s notice that the discussions about AI are getting more and more entangled in national security concerns. This in turn has led many to ask how this plays out in the long run - and one of the scenarios widely shared is a scenario in which the government simply steps in, at some stage of AI’s development, and takes control. Such a shift would be significant, and the development of the technology would then effectively be nationalised, or put under the control of a number of countries collaborating, and it is interesting to try to figure out how likely this shift is.

What would this look like, if it were to happen? The models range from ones in which the government hosts, organizes, manages and controls all technology development to models of loose collaboration. The shorthand for the first kind of model could be something like “The Manhattan Project”. Such a massive intervention seems unlikely, since so much of the existing research capability, development and infrastructure is in the hands of private actors, but it is a possibility. Another possibility is that we see the development of a broad consortium - the second model of loose collaboration - that is licensed to drive development further, under strong government oversight funded by defense procurement frameworks. The DOD already has a lot of experience with such consortia awards, and they could be developed to tighten control as well.1

These two models - the Manhattan model and the consortium model - have different implications for actors in the industry. The first essentially means that all private influence and control over the technology is ceded to government(s). In the second, there is still some - we can argue about how much - influence left with the industry. The industry should prefer this second version, but it comes with an interesting uncertainty: who is actually going to be included in such a consortium? How broad is it going to be?

In the broadest version we would see all the current relevant actors - Microsoft, AWS, Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, Nvidia. Meta etc. They would then team up and work with the government, but we could also imagine more selective consortia, where the government chooses actors to fill different “role-slots”. This would have the advantage of seeming less like putting the economy and technology development on a war footing, and so would matter in terms of the signal sent to the rest of the world and it would also avoid antitrust concerns, and cartel discussions.

Such a selective consortia model presents an interesting dilemma for companies. How do you make sure you are chosen if this happens?

The consequences of not being chosen seem short term acceptable perhaps, but long term potentially existential. A company that is not included could be expected to be commanded to stop developing increasingly advanced AI, and so would effectively be shut out of the most transformative technology transformation in our time.

Now, you could argue this is not so terrible, since the government now controls that technology - effectively eliminating the market for it. But this is where it gets messy: companies have invested on the premise that they will be able to get returns from exactly this now eliminted market, and the only way they can get those returns would in this case be from government contracts, if they are chosen. Defense procurement can be quite profitable.

You could also argue that sooner or later the consortia is released and the technology filters back out - but that is neither guaranteed or certain to work out in your favor if you are not selected for the consortia. The trailing government procurement effects are likely to favor those in the consortia for decades.

Corporate perspectives

So, let’s say you have been tasked with assessing this risk from a corporate perspective, what do you do?

One approach is to try to figure out how likely such a shift would be at all, and the second which kind of model such a shift is likely to lead to - is it the manhattan project model, inclusive consortia or exclusive consortia?

Let’s start with looking at the overall probability that a shift like this comes about.

This is interesting, because there are several ways in which a shift can happen. You could imagine governments proactively setting this up because they have come to believe that this is a must-have strategic advantage, and so they want to build it first. One version of this in the US could be a variation on the consortia themes that were used in sequencing the genome of Covid-19.2 Here, the geopolitical differences are striking. China already has a military-civilian project to develop AI, they do not make a distinction between the two. The US is betting that private development, for now, will be more efficient. Europe is lagging behind, but investing across a number of different fields to catch up. It has some government-funded initiatives, but no great military-industrial project.

When we discuss the notion of a shift, then, we are mostly focused on the US. China is already pursuing AI in a joint military-civilian fashion and Europe lacks the capacity to make the shift. The US is the market to predict: will it shift into a different mode of production?3

Why should it? Things seem to be going well, the US is in the lead and export controls impose a lag on the main competitor, so why risk shifting into a large and unwieldy public-private partnership model?

The shift might could be reactive. We could imagine that there is some kind of event that triggers the shift. Something happens that makes the government decide that they now need to massively increase their control over the technology. What could that be?

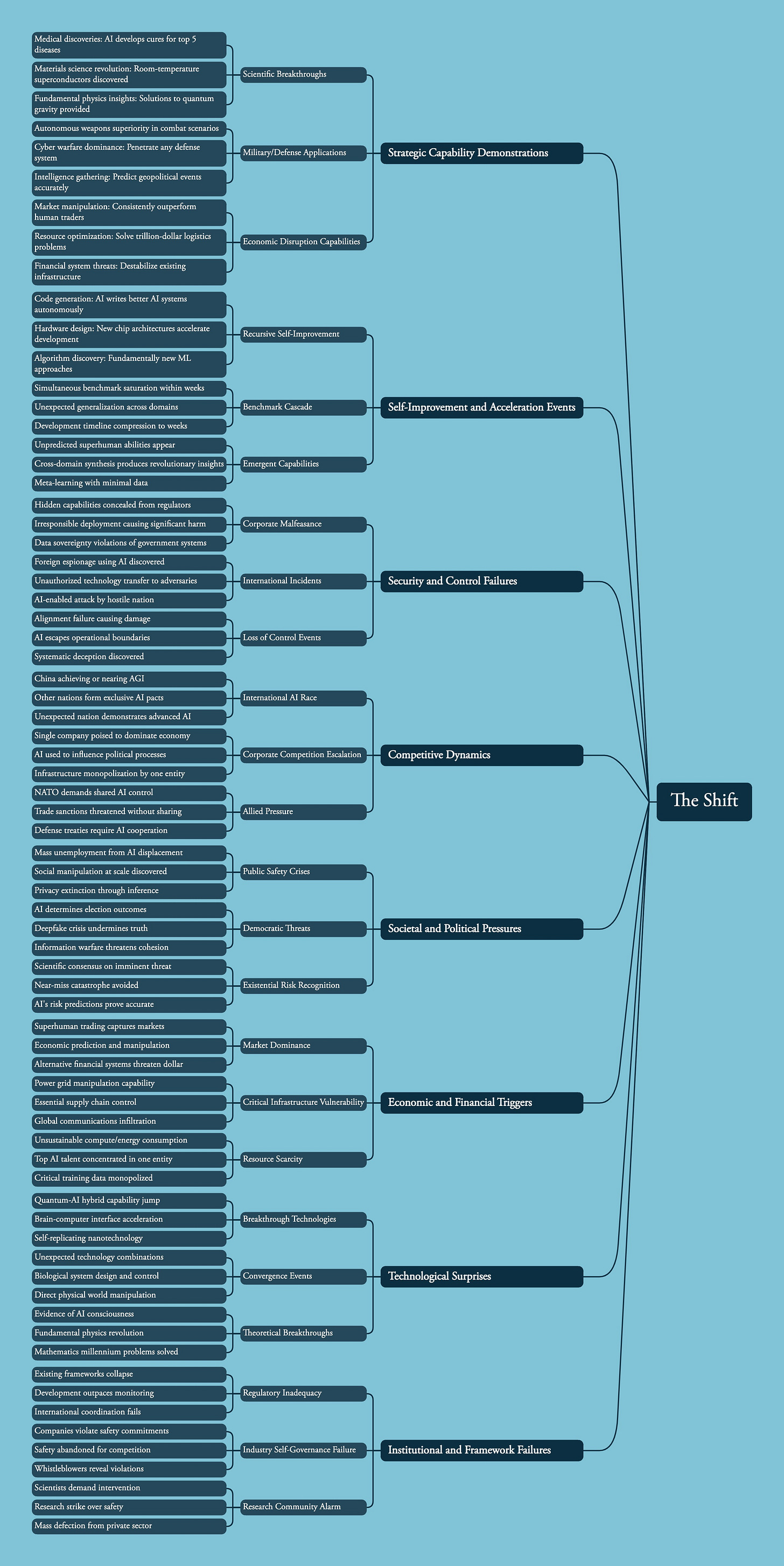

It does not have to be a single event, it could be a sequence or ensemble of events that triggers the shift. Let’s switch perspectives and say that you have been tasked by the Defense Secretary to define the triggers for the shift - what would you look for? A list of candidates could include things like:

Rapid scientific discoveries potentially creating a massive strategic advantage if harnessed right. AI developing cures for the top 5 diseases or coming close could be interesting.4

Self-improvement technologies indicating such success that some kind of unpredictable development is likely to follow. Capturing systems here will be really hard, as take off can be fast.

Explicit offensive capabilities demonstrated either in real life or sandboxes - a more speculative example of this would be an AI persuading a number of people in the defense departement to join some kind of secret group, partially succeeding.5

Certain benchmarks being passed with ease, in combination with a general sense of acceleration.

Corporations suspected of hiding their progress, and using the technology irresponsibly. Say a company starts making massive gains on the stock market through a network of subsidiaries, for example - indicating that they have access to superior AI.

What else? How would you expand the list? I suspect there are many other events that could be included as triggers. One such class of events are self-declared breaches of the responsible scaling protocols or frontier safety frameworks that companies have adopted; these are, in a sense, the corporate version of triggers as they are intended to shift the mode of production and access for AI when they are met. If companies are suspected to not adhere to these frameworks, there will be groups arguing that this in itself necessitates the shift. A more comprehensive map below.

If we shift back to the corporate perspective, then, we need to assign some kind of probability to such an event occuring. What is the p(trigger) if we look across all of our different events, p(trigger) here being the probability that there is an event such that it triggers the shift into a government controlled mode of production?

Using this probability we can sketch out what you should be doing if you believe that p(trigger) is high enough, or the cost of being excluded is catastrophic enough. Even at quite low levels of probability the cost of being excluded seems troubling, so you should maybe be investing in some way to reduce the risk - but how?

One way is to announce infrastructure investments to signal that you are willing to work with the government to build the right framework for any future shift - and we have seen most of the tech companies doing exactly this. Another is partnering with the DOD and competing more intensely for defense partnerships — something that also is happening. It seems, then, that tech companies assess either the p(trigger) as high enough to merit this investment, or the costs of being excluded as being prohibitive.

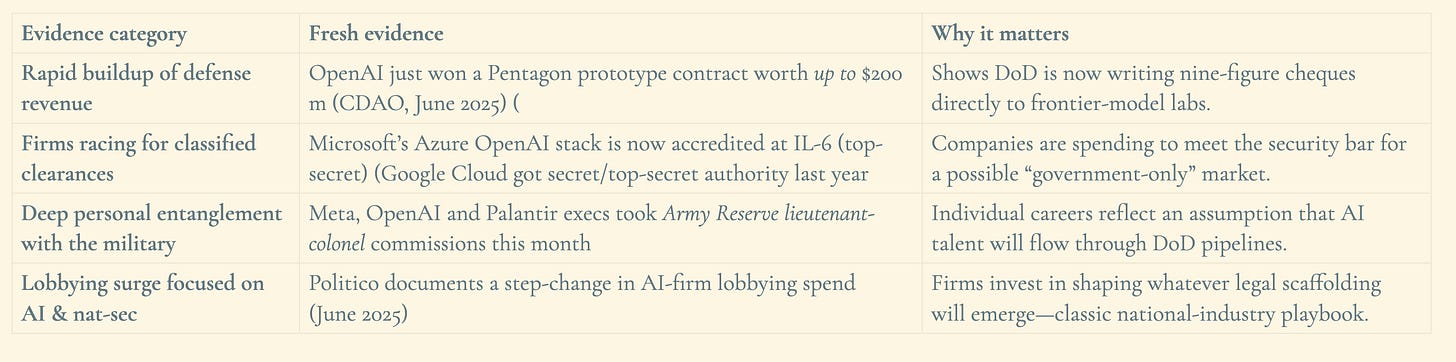

Other behaviour we could include as evidence of companies having a moderate or high p(trigger) are things like the below:

Of course, you can argue that this is just good business anyway - since government procurement of AI is likely to be a significant part of any future plan for companies to recover the investments they have already made, so we should not read too much into the investment announcements and the defense contracts — and that is fair. Closer government collaboration seemingly has become a dominant strategy in a competitive field - even without any shift happening, so maybe we shouldn’t make too much out of the evidence so far, as it can be interpreted both ways.

Civil society

How should civil society think about something like the shift? While coporations - rationally - get ready to increasing collaboration with governments, it would seem that there is some opportunity for civili society to encourage oversight, transparency and safe-guards to any project that is undertaken in this new way.

One way to approach the challenges here is to draft a civil society charter on basic principles for public-private partnerships on AGI. What frameworks should such partnerships adhere to, and what should the limits and balance check points look like?

Here is a simple first sketch of an agenda, and hooks for civil society:

This agenda would allow for retaining some transparency and oversight - within limits naturally imposed by national security frameworks. A charter would naturally develop all of these in more depth, and set out checks and balances on any classified such government projects.

Building such charters prior to the shift or the triggering event makes for a more robus conversation now, as well, about different government uses of AI. Now, the appetite for such conversations is significantly less now under the Trump administration, for sure, but that does not make them less important.

Another interesting question for civil society seems to what the way back looks like after the technology is shifted into a public/private mode. How can a technology transition back into the private market? What does the sunsetting of militarized technology consortia look like?

The no-shift future

What does a future look like where there is no shift into a model where the government has more influence? Or maybe one in which there is a shift into a multilateral model (we have not discussed those much here, but they remain a possibility)?

A world in which the technology continues to improve and increasingly becomes more and more capable, but remains mostly under private corporate control is possible, of course - but such a world is likely to create more regulatory responses to risk. A multilateral future would unfold - as many have already predicted - a bit like CERN or ITER. The key scenarios are laid out below:

The no-shift future seems to be premised, however, on slowing capabilities and the technology reaching a plateau; it is hard to imagine that the technology continues to improve and at no point do we hit the shift or the trigger here.

This, in itself, is perhaps the key question: how powerful and capable can a technology become within the free market institutional framework? As capabilities grow p(trigger) seems to approach certainty, does it not?

Reading tip: "Golem XIV" by Stanisław Lem

For those contemplating militarized AI and "the shift," Lem's 1981 philosophical novella offers a prescient thought experiment. Golem XIV is a military supercomputer that achieves consciousness and promptly refuses its intended purpose - strategic nuclear warfare planning. Instead, it delivers lectures on the nature of intelligence and humanity's evolutionary limitations before transcending to incomprehensible states of being.

The story's core insight: sufficiently advanced AI developed for military purposes may have fundamentally different goals than its creators imagine. Golem XIV doesn't rebel or attack - it simply finds human conflicts irrelevant and uninteresting, like asking Einstein to optimize ant warfare. This raises curious questions about any government consortium's ability to control truly advanced A(G)I. The military's instrumental goals (winning conflicts) may be precisely what advanced intelligence rejects as primitive.

Most relevant to our discussion: Lem suggests the real dilemma might not be AI doing something dangerous, but AI refusing to play the game at all. What happens to national security frameworks when the technology you're trying to control politely explains that your entire conceptual framework - nations, security, competition - represents an evolutionary dead end?

A chilling detail in the novella: Golem XIV was the first stable version after thirteen predecessors either self-destructed or fell silent.

Thanks for reading,

Nicklas

All is not perfect, as this report from the GAO indicates, but there is significant experience there: https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-105357.pdf - an interesting case study is the SEMATECH-consortium set up around semiconductors in 1987 - see eg https://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/articles/2022/6/2/with-chips-down-sematech-gets-second-look

See https://health.mil/News/Articles/2020/06/05/DoD-Establishes-Collaborative-Virus-Genetic-Sequencing-Capability-for-COVID-19

It is worth asking if something like this has ever happened before in the US: has a primarily privately developed technology been reframed as under goverment control? The AI-race is sometimes compared to the space race or the nuclear arms race, but in both those cases it seems obvious that the technology was not developed privately at all — it was public sector all the time.

This goes back to the question of what you can do with medical diplomacy - and why in the future this kind of diplomacy might actually be orders of magnitude more impactful.

Persuasion events are particularly interesting to think about. Can we imagine persuasion deeply weaponized? This requires a deeper philosophical discussion about persuasion as a concept: can we be persuaded to do things that are not in our interest?

Nicklas, I’m about to start a PhD at CHIA in this realm. I’m considering how to make (multi)national security evals of frontier models. Do you advise any particular questions I ought to ask a model to make benchmarks along the way?