Unpredictable Patterns #66: The art and practice of review

Why real change has roots in the past, on the allure of anticipation and the key to some kind of happiness

Dear reader,

Today’s note is about a practice - review - that I think we all know is good, but to some extent neglect. It is a key practice for change - and understanding it may in many cases be much more important than exploring how we think about the future. In fact, our willingness to think about the future sometimes overwhelms the need for thinking about the past. Let me know what you think.

The allure of anticipation

We are often caught in anticipation of the future, so often so that we forget about the value of the past. It is easier to sit down on a Sunday evening and think about the week that is coming, than to think about the week that was. This is simply a part of the human condition - we are aimed at the future, in a way - and so we prefer to live there rather than in the present or in the past.

In fact, living in the past, caught in sentimentality or nostalgia, is often thought of as a disease - an inability to move on and focus on what is next.

Yet, the real key to changing the future lies in understanding our own past - across a lot of different dimensions: the personal, professional, creative, romantic - the past contains keys and patterns that show us who we are and how we act. The past is the source of the willpower that we need to change our behavior and to evolve.

And at the heart of this lies the surprisingly simple and yet tremendously powerful ability of review.

When we review something - when we look at it again - we can see it from a third point of view, not from the heat of the moment and not from the anticipation of the future, but from the vantage point of experience. We get to see it from afar.

Making review a part of our habits and life, is perhaps the only way that we can really effect any change. From the simple daily reflection in a journal, to the weekly review to the exploration of a period or a life in whole - reviewing is the key to ensuring that we break free of the patterns that we are living.

It is only in review that those patterns become clear and visible to us - it is only then that we can see where we make the same choices. And seeing them lets us eliminate the power they have over us. When we see them they open up to examination and to change.

Daily review

The daily review - the moment of reflection in a diary or the quiet conversation with a friend - is the basis of understanding ourselves. It is the first step in figuring out the why-questions that we always face: why did this happen? Why does this keep happening? Why am I thinking in this way? Why are we continuously so bad at this?

Daily personal and professional review does not have to be lengthy - it only needs to take a few minutes to jot down impressions, questions, feelings and observations. Often when I do this I find that I spend more time than I intended - it is as if I find that I really wanted to think more about it: like meeting a friend that really wants to talk something out. The time spent in daily review is time that connects moments, and allows us to see the line of moments that connects us with the present - and so gives us an ability to expand our now.

The now we experience is the narrative moment that we inhabit - the story we are a part of - and it can be very, very small - we may feel that we are just hap hazardly stumbling along through our days - or it can extend weeks, months or even years back. The idea of narrative depth is the idea that we experience life differently if we feel that we know our own stories.

This is equally true for organizations, of course. The ability to do professionally what we do personally does not diminish the personal, but makes the professional more meaningful.

The distinction we sometimes make between work and life hides the larger truth that we spend a lot of our time on work, and so to integrate that time into a meaningful whole requires that we think through our professional day within the context of the personal. This is not to suggest that they are the same, but it is to suggest that they are deeply connected in ways that will vary from person to person.

The daily review allows us to weave that moment into a longer now, a now that sustains a narrative and a continuity in which we can find out what we want and who we are to a degree that we cannot if we get stuck in anticipation of the future.

Weekly review

The weekly review is much less common. Perhaps because it requires a brutal kind of honesty, a space in which we can dispassionately view our short comings as well as see the cracks in our victories. To review a week is to look closely at one of perhaps 4000 weeks that we get in this life.

The way we spend weeks and the nature of those weeks contribute to a clearer view of how we are spending our lives and that is a frightening thing - and it should be.

A week is no small thing.

In weekly review we get the chance to practice our own ability to see clearly: what did we get done and what was left undone? Where did we fall short, and where did we excel or at least try to?

At one point in my career I had the fortune to work with a person who I summed up my weeks with, and unfailingly he would be able to point to the good things, without neglecting to see and acknowledging the bad - and he always concluded that it ”had been a good week”. And he was right, but it was also because his review made it into a good week. That taught me something important - the way to approach review is not with self-loathing, but with a certain kindness.

This kindness is a pre-requisite for the review, and it is what allows us to see the world more clearly: when we look at our own past with a certain kindness we can also see the failures and missteps in a way that show them for what they are: human failings and weaknesses.

The key to enjoying the weekly review is to see how it connects those 4000 week’s and to do so in a spirit of kindness.

Monthly and yearly reviews

I almost never sit down and do a monthly reviews - months seem to me to be strange units that I cannot organize into any cohesive patterns - seasons, yes, but not months. I suspect that there is a personality trait here - some live in weeks, others in months - but for me the week is understandable, the month is not. The same holds for quarters and half-years.

I do understand the yearly review much better, though.

A year is a real unit of time for me: if I get 80 years, I am lucky - and so looking closely at the years that pass and ask if I think that I have spent the last year well - and what I have to show for it - is a practice that I got into early in my life.

Over time my yearly reviews have changed - from focusing on what I wanted to become, to what I wanted to be - for myself and others. It is probably because I am entering the springtime of old age, but I also find it an interesting distinction for another reason: rather than look at accomplishments I now look at improvements in my way of living.

And years are not open to the same simple judgment that weeks are - it makes no sense to judge a year good or bad, a year is so much more. When I look at the last year I ask if it made sense. Did the last year make sense to me, given who I am and wanted to be? Was it a year lived in the emotional and intellectual key that I wanted to live in?

And years make sense in so many different ways. Sometimes - unfortunately - years will be hard and filled with sorrow, but that sorrow can make sense - it can matter and change us and open up new paths. But a year where I have remained numb to everything and not listened to the changes, that is a year that does not make sense - a year in which I have not truly lived.

I have had years like that, of course - everyone has - but having had them, seen them and recognized them for that I now think I can start to sense when it is happening. It is like a small dissonance in music - and I can move to correct it.

One way to think about it is that years can come in minor or major keys - just like symphonies or fugues - but that this does not make them bad or good. A year in the minor key may be as important and - in some sense - beautiful as a year exuberantly spent in the major key.

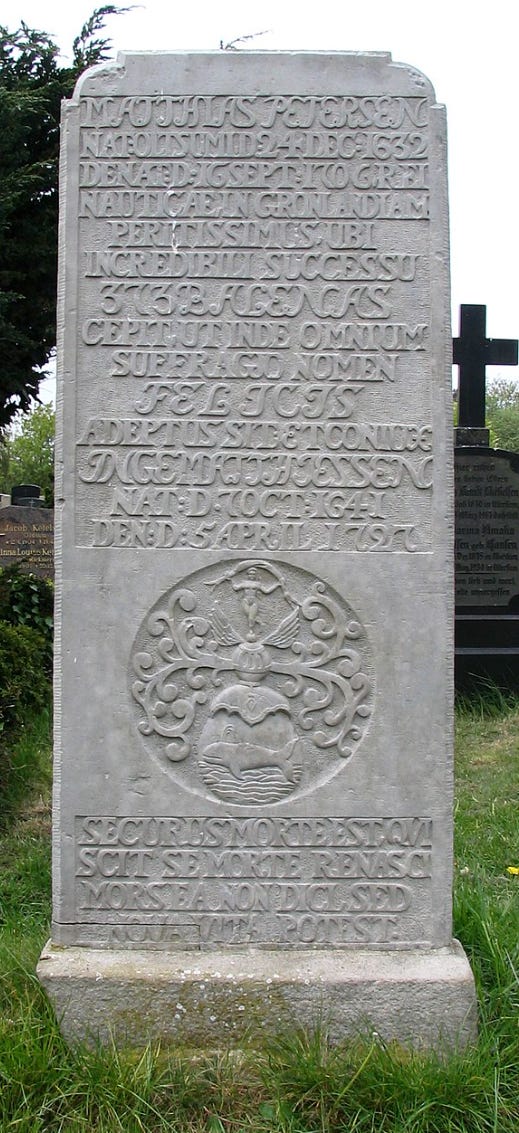

Life review

Aristotle (you did not think we would not come to him, did you? We always do!) says in the Nicomachean Ethics that we can judge no man happy until he is dead. The idea is simple: happiness is a quality that can only be predicated of a life in whole - not of a day or a year. Happiness, in this sense, is about the nature of all of our days, weeks, months and years and how they fit together.

As we sum up the lives of those that we know, and have passed on, we can make such judgments - but we will never be able to do it for real about our own life. That does not mean that we should ignore this perspective, however.

Someone once told me that they had been to a retreat and the first task they got from the teacher was to write their own obituary. I have since learned that this is not an uncommon exercise in different programs for self-improvement and personal development, but at the time this idea really brought me pause.

Writing your own obituary is making that Aristotelian judgment about your life: was it happy? Was it meaningful? And if so - how do you know?

The first question you will have to face is a simple one: who is writing the obituary? Is it your friends? Your colleagues? Your children? All of them? And then - what are the things they highlight?

Will they write that ”you always had time for the people close to you”? Or will they laud your professional accomplishments? Will they do a little of both, and if so with what balance?

Try it. But don’t dwell on it.

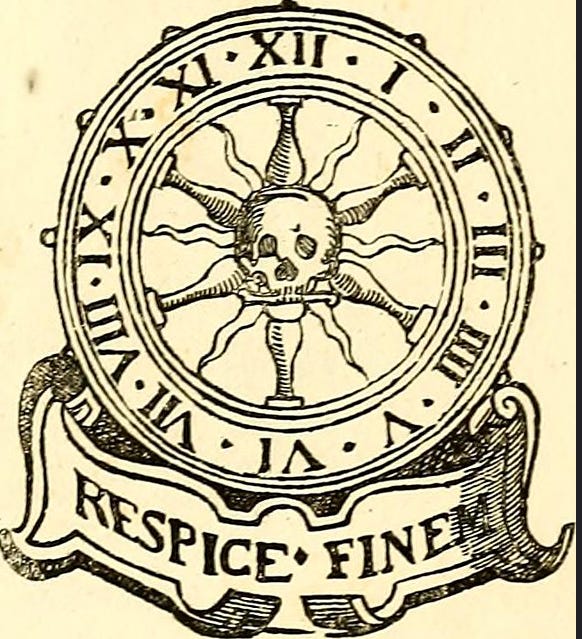

The ”memento mori” is really a command to not just remember death - but to review your own death. Remember that you shall once die, and when you do - what will then be the patterns that people see?

Reviews and retrospectives in work

There is something existential about the idea of review - but that does not mean that it is any less useful in daily life. The ability to review our work and to look at it in retrospective is as powerful there as it is elsewhere.

Sure, organizational politics and personal tensions make it a fraught project - you do not want to insult people by pointing out mistakes they made, and you might end up rarely, if ever, looking back at projects and events in your work life.

That is, of course, a horrible waste of insight.

A good review or retrospective into a project or an event is usually a way to really understand not just the thing that happened, but the nature of the organization you are in. An organization that refuses to do so - either explicitly or discourages it because of an inability to find value in its past actions - is likely to fragment into fabricated histories.

Sometimes called ”post mortems”, retrospectives are ways to explore our organizational past and really look at what happened. A few basic rules are necessary to observe.

First, any retrospective is uninterested in blame. In a functional organization blame flows upward, and praise flows downward. The accomplishments are shared by all, and the failures owned by those that lead. But this is even more important in a retrospective, since the spectre of blame distorts everything and makes it impossible to learn from the past. And it also reflects a deeper truth: individual action may be the cause of an event, but that individual action was made possible within the framework of the organization, so the reality is that individual action is never a root cause in any meaningful way. Understanding what happened is always much more important than understanding who it happened with. (But, I hear you say - cannot individual incompetence be a problem? Of course, and yet: how has the organization allowed for it to impact outcomes? In the majority of cases that is the question - not whose fault it was).

Second, ensure that the successes are explored as thoroughly as the failures. Successes are almost always to some degree due to luck, and understanding where they could have shifted into failure is the best way to really explore the way that the organization learns and acts.

Third, seek the truth. Again - this is that particular mindset that is required of the review. A kind, but brutal honesty that looks at what is there, not what we want to find. It is hard - but once mastered a brilliant tool to unearth real insights into how an organization can evolve.

And that is the key: evolving into something new - understanding the past and the patterns that make us, so that we can change them.

We have mentioned the pre-mortem many times in these notes, and it is reminiscent of writing your own obituary in a way: looking at the projects undertaken and understanding how they will be remembered and what the salient details and features will be seen to have been, is a great way to not just explore projects and idea, but even whole organizations.

What should be written about your organization once it disappears? Because organizations also die, and perish - so what should the organizational obituary look like? And who should write it?

So what?

There is a very simple question here: are you reviewing the past to a reasonable extent? If you are - congratulations. My experience is that the anticipation of the future often overtakes the review of the past, dooming us to live in future moments uninformed by history.

Otherwise: set up a schedule of reviews - for yourself, with others, and then see what it looks like. Try it - and see where it becomes hard. The points at which review causes us pain are points that are more important than we think. Why are you hesitating to write about your day, week or year? Why is a certain project off limits for a retrospective? Our hesitancy reveals something important.

And, finally, then: it is really only in the review we can find that Archimedean point from which we can shift the earth and change ourselves and evolve - either as organizations or individuals.

Thank you for reading,

Nicklas

"In a functional organization blame flows upward, and praise flows downward" -- lovely.