Unpredictable Patterns #46: Tactics: the neglected sibling of strategy

Why you need a chief tactical officer, how haiku teach us about tactics and why fugues are great devices to learn to make decisions

Dear reader,

Darkness is underrated. The sun now sets at 3.30 pm and the season is almost custom-made for deep reflection, reading, mulled wine, napping, more mulled wine and then more reading. It is cold outside, and it is lovely. This week we will try something new: we will discuss why we always undervalue tactics in thinking about organizations - and why this oft-neglected younger sister of strategy may actually be the key to thinking concretely about our strategic choices!

Tactics

Tactics is often the belittled younger sibling of strategy. To say of someone that they are ”tactical” is often taken as criticism - and intended as such as well. But tactics grow in importance in complex systems and environments, and in some cases all you can be is tactical - and this what will help you win.

Books are written about strategy, and grand strategy - but few books are written about tactics. It is as if we believe that tactics is simply not important enough - but if we examine how we spend our time, I think it is fair to guess that most of us spend 5-10 times more time in tactical considerations than in contemplating strategy.

So why is tactics so unexplored? One reason is that we do not really know what it is — when we dismissing something as tactical we are saying that it does not really fit into the larger pattern - or that it is just an accident that it does fit in to that larger plan. A tactical question can be resolved in many ways, a strategy question in only one - hopefully superior - way. Tactics is dismissed because it is so common, so everyday, so present in all our decisions. Yet, these are the very reasons we should discuss tactics in much greater detail.

Tactics is the art of arrangement - to set things up in the right way, to ensure that they then play out in the most efficient game. Tactics are the site of conflict, where strategy meets reality - the place where all plans go to die, to follow von Moltke’s wry observation that no plan survives contact with reality.

But what then happens is that the plan changes, and it changes through, yes, tactics.

The art of arrangement - the way you arrange your pieces in chess or your forces in war - requires attention to detail. Tactics is really much closer to logistics than strategy will ever be. Your set of available tactics are determined much less by your strategy than your logistics.

Attacking a foreign military leader or assassinating them is an example of tactics. Cutting off fuel to a fleet, or ensuring that you spread the flu in the enemy camp - tactics again. Tactics are the means through which your strategy is implemented. All conflicts, games - all wars - are won through tactics. Your strategy is important, because it helps you direct your tactics - but the tactics are what will really win you the war.

Tactics is what allows the composer to play a symphony, it is the choice of instruments and the pieces of the composition they will play.

Let’s talk about arrangement. Arranging something is putting it in the proper order. A chef arranges the kitchen for a dish, a musician will arrange a piece for the best possible performance by a specific orchestra. A good CEO will arrange the resources of the company so that they reinforce and enable the strategic progress of that company.

Arranging something is seeking order.

The idea of order is tremendously deep and generative, and one that anyone interested in complex systems would do well to spend plenty of time on. The idea of order is the idea that there is something about a particular state of a system that changes the nature of the system as a whole - that there are states of the system that are more meaningful and important than other states.

The notion of order is also connected strongly to the idea of a beginning - that there is a state of affairs that is more original, more basic than others - and that exploring that state of a system will give you advantages in different ways.

Tactics is about deploying order to win over less ordered systems.

One version of order-as-tactis is self-discipline. The discipline to keep to a single objective and ensure that this goal is kept front of mind for everyone dealing with a project of any kind. The disciplined organization wins over the distracted, and will be able to take on greater challenges than an organization that is constantly giving into its desires and whims,

You could argue that what Steve Jobs brought to Apple was not so much design, creativity, out-of-the-box-thinking as it was discipline. The ability to focus efforts on a small set of products that were tightly integrated. And so you could even argue that one of the most important metrics for investing in, or joining, an organization is its self-discipline. Is it able to take its lumps and continue down a single path to its objectives? Can it ignore the temptations and distractions? Is your organization able to keep its attention directed at a single thing for more than a quarter?

A tactical organization is disciplined. Strategy can roam freely and seek new solutions, invent new paradigms and seek entirely new capabilities. A tactical organization seeks to achieve its goal within the parameters set at the outset, and uses discipline to ensure that the capabilities it has access to are enough to get there.

The tactics of Bach

One example of how tactics create order that ends up in something extraordinary can be found in Johann Sebastian Bach’s compositions. Bach was famous for writing extremely complex music, and some of the music he wrote was so complex as to make musicians today note that it should be ”read not performed”.

Bach wrote, among many other things, a special form called a fugue.

A fugue is a complex piece of music where every voice is connected to and determined by every other voice. The word ”fugue” is derived from ”to flee” and the fugue is, in many ways, a chase where different voices respond to and correspond to each-other. The end product is a complex piece of music where every new voice obeys certain rules and relates to every other piece, as can be heard in Bach. A fugue is based on a dialogical process, where voices respond to each-other and co-construct the end product.

Fugues are interesting also because they usually have a subject of some kind, a sequence of notes that seed the fugue as it evolves in to a masterful piece of music. That means that there is no single right fugue for a subject or theme, but the theme has to be respected in the design of the fugue - it weaves through the many different voices.

This is a useful way to think about organizations - what is the subject and theme - and how are the different functions harmonizing in contrapuntal order around that very them? And the answer to this question is dependent entirely on the tactical quality of the organization. A great tactical organization is able to match point against point in harmony in service of the subject or theme - and a lesser organization will quickly start to play out of tune.

It does not matter that organizations may agree on the subject or theme or objectives - if they are not able to build a greater harmony contrapuntally around it, through great tactics, they will fail.

Our choice of tactics also limit us - creatively. Most creativity is enhanced by limits. The musical form of the fugue is circumscribed by rules in all directions. Those rules are what give rise to masterpieces like Bach’s. The limits really reveal the master, and the limits are the tactics.

Mastery is dependent on tactical limitations.

The tactical haiku

Another example of this is meter in literature. Meter is a tactical device. You may know the message you want to convey, and the story you want to tell - but when you choose a meter you can draw upon an entirely tradition of writing. Using the same meter as Homer allows you to set your story against the ancients, breaking the meter allows you to cry away from all rules. Dismissing the language of art in favor of the language of commoners allows you to upset the entire order of things (as Dante did when we wrote the Divine Comedy in Italian, not Latin).

Good organizations are disciplined in the sense that they work under a discovered or constructed rule set like the rules of contrapuntal composition or a specific meter. Or they break those rules in an equally disciplined manner. Dante did not abandon meter when he shifted language from the learned Latin to Italian - he developed his own specific meter for his poem.

The order you operate under is the key tactic you are deploying. The limits you set on yourself are the real sources of strength that you can draw on.

We have all experienced this, probably in school, when forced to compose a poem or, say, a haiku. The idea of the limitations first strike us as ridiculous, and then, slowly, we rise to the challenge. The haiku format seems insane at first, but then invites a special use of language, a use that can express things that we would not otherwise be able to express at all.

And the magic of the thing is that we can express anything in a haiku - the meter itself is not strategic, it is a tactic. It gives us an efficient limit - an arrangement - as well as a means of expression. This is what all good tactics help us do.

Strategies are often unique and individual, but you can acquire libraries of tactics.

In chess, any somewhat experience player knows what a fork is. A fork is when a single piece simultaneously threatens two different pieces and the opponent has to choose to sacrifice one of their pieces. A fork is a tactic, not a strategy - it is a reusable pattern that you can look for in any game of chess.

It is markedly different from, say, the strategic insights of Sun Zi. Where master Sun suggests that we know ourselves and our enemy, the fork carries no such wisdom - it is just a pattern that recurs and creates a small advantage. We can imagine threatening an opponent in two places and so forcing them to choose what to defend in almost any game or any conflict. Knowing ourselves and our enemy is applicable to all conflicts, but suggests no arrangement of our forces or resources.

Tactics are like legos, they can build into anything that you want to create.

Studying games, music, art, literature - anything - is helpful in learning tactics. The study of tactics is the study of limitations at the edges of our pursuits, the creation of limits for others - the fork is a case in point: it creates a limitation for our opponent and generates a necessary choice - what is sometimes called zugzwang in chess: a forced move.

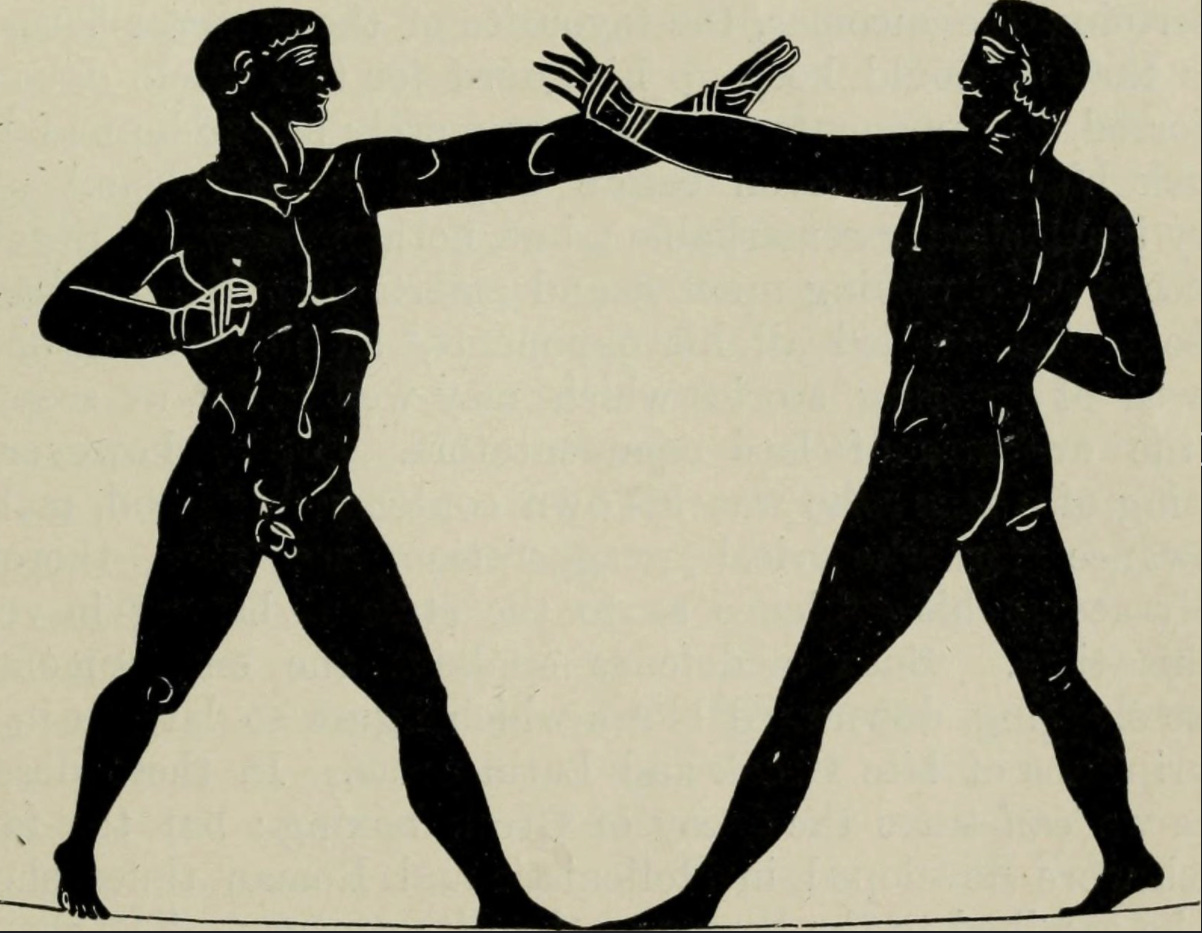

Tactics are like techniques in martial arts, boxing or wrestling - a set of possible responses to ever-changing situations, individual techniques that express a deeper principle of human interaction - like ikkyo in aikido, a techniques that avoids meeting force head on, but instead redirects it from the side into the attacker to force them to take responsibility for the force of their attack. And every technique in aikido can be applied in a multitude of contexts, a pattern to limit force.

Libraries of tactics

The best tactics force the moves of our opponents. Ideal strategy - something we will never attain - is implemented in a set of tactics that force every single move of the enemy to their ultimate loss.

Assembling and collecting a library of tactics is a great way to think not about strategy, but about how you implement your strategy once you have arrived at it.

One of the greatest libraries of tactics is called the 36 stratagems and it is a sadly neglected book of Chinese strategy. Whereas everyone is familiar with Sun Zi, few people have spent time reading the 36 stratagems - and yet this is the book that provides the legos for building the strategies in Sun Zi.

While called ”stratagems” the 36 patterns described are really tactics. A few examples include:

Borrow a corpse to resurrect the soul. Take an old technology or institution and revive and repurpose it for your own purposes.

Point at the mulberry tree while curing the locust tree. Chastise others by proxy, signal to them that you are on to them through leveling the criticism at someone close to them.

Create something from nothing. Well, this one is easy: lie!

Hide a knife behind a smile. Fake friendship and then move against someone.

These tactics are ancient, recurring patterns in human affairs, and really - all tactics are! The study of tactics is the study of human interaction at a certain resolution: not the large scale, long waves of civilization, but the move by move human interactions of the everyday.

And let’s be clear: not all tactics are devious. When we study game theory we quickly realize that collaboration is a great tactic in repeated games - something that allows us to build trust, friendship and flourish as human beings. Sound tactics are probably more often collaborative than divisive - and they limit ourselves more than our opponents or collaborators.

Assemble your own library of tactics - and you will find that some work better than others in your hands. Some almost always fail - and some are the keys to your success.

Shifting tactics as competitive advantage

Blitzkrieg was not a strategy. It was a tactic - to use speed to overcome the enemy and do so in an overwhelming way. This tactic changed the game of war and led to a very different style of war than most were used to. The use of air power is a similar example - not a strategy as much as a tactic that then allowed for the formulation of a new strategy.

So why do we then focus so much on strategic competitive advantages, if we know that they are made up of tactical advantages and shifts? Again - the reason is that we prize strategy as a more fine art than tactics, we are deceived by the abstraction of strategy and so undervalue tactics - but we can change.

The question of what new tactics we could deploy is often a more useful question than the question of what new strategies we have available to us, and as we have shown this question is really the question about how we can arrange our resources, how we can use a new order of things to make progress.

The dimensions of strategy here are interesting - we can easily see, as in the case of blitzkrieg, that speed is one. Doing something faster than anyone else is a tactical advantage - but being able to really spend time on something and wait can equally be a tactical move of great value. Another dimension is focus vs dispersal. Clausewitz taught that we should always strike with full force at the center of gravity of the enemy, so Al Qaeda changed its structure so that there was no single center and deployed asymmetrical attacks.

How concentrated or dispersed we are - the density of our organization and operations - is another tactical dimension. A third is variation - the many different versions of what we do can be a sure way to gain a tactical advantage. Mutating fast in many versions is the key tactical advantage that a virus can deploy - and so the rate of mutation seems to be a good candidate for a third dimension: speed, density and the rate of mutation of our operations then make the key tactical dimensions - and we can index our own organization on these three: how good are we at moving with speed, how well do we adapt our density to the challenges we face and what is our rate of variation and selection? And how strong are those selection mechanisms?

The answer is an outline of our tactical capability overall.

So what?

The focus on strategy has detracted from tactics and often leads us to miss the meso-level of complexity that we operate in. We get the macro-level - the strategy, and we devote enormous resources to thinking about corporate strategy, but name one company that has a Chief Tactical Officer? We also get the micro-level of individual projects that we run within our strategies, and that are supposed to contribute to them - but we often lack an understanding of tactics.

Thinking about tactics - recurring patterns that limit us or our opponents in different creative ways - is a key to innovating in organizational behavior, and something that we should spend more time on. So what can you do?

First, explore your tactical library. What are the tactics you deploy and how have they worked historically? What are some others tactics from games, war or business that you could add to your tactical library? When you have built a tactical library you should make sure that it is a part of your everyday decision making - what is the best tactic to respond to the challenge you face today?

Second, explore how others are arranging their resources and the order they create. This is their tactical foot print and it is there for you to study and explore. Understanding the tactical habits of others is a great way to predict them.

Third, conduct discipline audits. How disciplined are you in pursuing your key goals? Individually? As an organization? Where do you succeed best? If your organization was on a diet - would it cheat often? Always? Who in your business is the most disciplined? Why?

Fourth, convey not just strategy discussions but tactics discussions. In planning or making difficult decisions do not just relegate the tactics the last step (”so we have decided to do this, can you figure out how to best do it”). Consider tactics as at least as important as the strategy and the overall solution to a problem. If you spend 80% of the time solving a problem and 20% of that time on the tactics of how to deliver the solution you are succumbing to tactics-neglect!

As always, thank you for reading, and good luck with your tactical progress!

Nicklas

Wonderful read. I would argue that while Jobs focus was very much his secret sauce, what pushed me over to love from like was 'Oh, and another thing'.