Unpredictable Patterns #45: Victory and other failures

Luttwak, strategy of success, regularities and patterns of policy and the limits of analogy

Dear reader,

One of the great things with having the privilege of writing these notes is the feedback I get from you - please keep that coming, I learn a lot from it. The last note, about waiting, generated a few interesting comments and I want to call out one in particular, a comment on innovation and waiting and the so-called incubation time and how important that is. It is nicely captured by T.S. Eliot: “Waiting, as represented by silences, gaps, and distance, allows us the capacity to imagine that which does not yet exist and, ultimately, innovate into those new worlds as our knowledge expands.” This idea, that innovation is born out of waiting, struck me as very intriguing! So thank you!

In today’s note we will look more closely at strategy and success -and the dangers of victory.

Victory, success and other risks

Historian and thinker Edward Luttwak is one of the perhaps most interesting writers on the nature and complexity of strategy. His book Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace is unique in its analysis of the often paradoxical nature of conflict, and he introduces a lot of new and interesting concepts. One of the key concepts that Luttwak has introduced into strategic thinking is the idea of ”the culminating point of success” - and we will get back to that - but to get a sense of his style of thinking we will begin with another example:the way vulnerabilities are created in any strategy through the basics of economics.

Luttwak notes that the modern army relies on the economies of scale available through modern manufacturing - and this in turn creates a homogeneity - the weapons produced are the same, the helmets look the same — and this in turn means that it is much easier to detect the vulnerability in the system. It is produced by the economies of scale!

It is worth thinking about this — any organization will seek standards, regular patterns, homogeneity for economic reasons - but this also creates clear vulnerabilities that an opponent can exploit. Luttwak writes:

”But for military equipment that must function in direct interaction with the enemy—within the strategic realm, that is—homogeneity can easily become a potential vulnerability.

Luttwak, Edward N.. Strategy (p. 59). Harvard University Press. Kindle Edition. ”

This brings to mind a plot element that we often laugh at in movies: the baddies often have an awesome weapon, with a very clear and obvious flaw. The Death Star in Star Wars has a vent that you can send a missile through and blow the whole thing up, the battle droids are controlled centrally through a single control station — and we ask, quite rightly, why on earth anyone would design a system that way (now, in new Star Wars canon the design flaw in the Death Star may well have been intentional, but you get the point). But this plot device is far more realistic than we assume - because of exactly the reasons that Luttwak cite: efficiency and economy generate homogeneity and so create disastrous vulnerabilities in any system.

What the movies do is just accentuate this point - by making the vulnerability incredibly obvious. But you could just as easily imagine, say, that the battle droids were not centrally controlled, but all operated on the same frequency - or had a compound in their batteries that reacted badly to cold or…you get the idea. The vulnerability would just have to be a regularity or homogeneity produced by economic considerations.

The value in Luttwak’s observation is obvious: we can detect vulnerabilities in our products, systems or organizations through looking at regularities and recurring patterns - in fact, we can learn something about the fundamental nature of a vulnerability: it is often based on a regularity! A recurring pattern almost always suggests a weakness. And this is not just true for weapons systems - it is also true for figuring out things codes and cyphers. Part of the work with cracking the Enigma was finding regularities in the German messages. The simplistic, and almost entirely false, story is that the Germans ended all messages with ”heil Hitler” and so from that you could start to back out the code - but the reality is that other regularities like weather reports and standard templates for orders helped find patterns that recurred and through these the codes could slowly be cracked.

And this should not surprise us - this is at the heart of scientific thinking over all: discovering and exploring regularities is the key to understanding the world! The world reveals itself through the recurring patterns and homogeneities. It hides in complexity and randomness. The veil of Isis - reputedly hiding the true nature of the world - is woven out of chance in patterns that do not repeat.

This does suggest an interesting conclusion, however: by mapping regularities in our own behavior or in the behavior of others we can start to understand where there might be points of intervention, vulnerabilities or opportunities. By understanding the recurring patterns of our business or industry we can start to craft a strategy that draws its power from, rather than is challenged by, those same regularities.

What are the deep, recurring patterns of your organization? Are there reactions to outside events that always play out the same way? Are there responses that are always too late? Do you have decision making patterns that create crippling uncertainty when you really need to act? Are there good patterns that should be amplified? And what about the patterns you see in competitors, with consumers or regulators?

A simple example: a repeat pattern for many platforms when it comes to controversial content has been to first respond weakly if at all, and prefer not to act, and then to be pressured into acting and then act - but too late and either too much or too little. This has made it really easy to attack platforms: find controversial content and write an article about it and push that article with others. Then wait for them to bundle the response and lose in credibility every single time. This is a known form of attack and still the pattern often repeats, again and again. Regularities in content moderation become vulnerabilities for those who want to attack platforms.

Part of what we do - or should do - as public policy professionals is to explore recurring political patterns, and examine them closely. The study of these patterns is often as important as relationship building, since the patterns let you know when those relationships will be most effective - and if you want to effect real change, knowing how change happens is key.

There are, of course, a lot of different political patterns - but they are not infinite. There are few enough that it makes sense to start discussing them and thinking through what they mean and where they are open to dialogue and discussion, and where they are closed. These patterns can also be thought of as cost structures: it is much more costly to try to influence legislation at the end of the process than in the beginning, and it is often much more expensive to create compliance structures than to engage in self-regulation o even co-regulation of different kinds.

The study of regularities is key to strategy, and yet often curiously undervalued.

Victory and other problems

One other point we find in Luttwak is one that he has extended from Clausewitz - the idea of a culminating point in all conflict. This point is one in which the army can extend no further without breaking its logistics lines and so slowly disintegrating. The culminating point is the point at which defeat can be snatched from the jaws of victory - if you continue the advance you slowly dissolve and the quickly collapse.

Luttwak suggests that this is true for all victories, and that within all victories lie the seeds of defeat. The idea is simple: the very thing that drove you to victory if over-applied will also lead to your eventual defeat.

This is not a new thought - but it should be a sobering one for most organizations. If you look at your strengths now, the greatest challenges you will see in the future will flow from those very strengths as they overextend your position.

An open platform attracting millions of content creators wins through its openness, but then is plunged into content moderation challenges as they win. A walled garden manages to maintain its competitive position but then opens itself up to antitrust concerns. For tech companies there is a theorem here that is worth thinking about:

Your technological design successes contain your regulatory costs and vulnerabilities.

It is not quite the case that all technological success leads to regulatory defeat, but it is close enough for new and fast-growing companies to pay some attention to: what are your greatest technological successes and how will the impact your regulatory context?

Luttwak’s point goes beyond specific strengths and weaknesses, and he makes an oft-repeated point that is, unfortunately, often quickly forgotten:

Leadership too can be greatly enhanced by victory, or just as easily undone. With success already achieved once or several times, the impulse to drive men into the dangers of combat may be spent. In the defeated army in retreat, leaders may have lost all authority; but if that is not the case, bitter memories of recent failure may drive them to demand more from their men and give them the energy to do so. But when it comes to the skills and procedures of war, the balance of possibilities is not even: victory misleads, defeat educates.

Luttwak, Edward N.. Strategy (p. 33). Harvard University Press. Kindle Edition.

Victory misleads, defeat educates! This may be one of the most important insights in all of strategy, but it is often forgotten because we like to claim victories and renounce defeats. But it also contains a deeper truth: the constantly victorious is most likely also quite misled - and believes in their own myth. Luttwak again:

With victory, all of the army’s habits, procedures, structures, tactics, and methods will indiscriminately be confirmed as valid or even brilliant—including those that could benefit from improvement or even drastic reform.

Luttwak, Edward N.. Strategy (p. 33). Harvard University Press. Kindle Edition.

We can extend Luttwak’s point with a model from evolution. A company that is constantly victorious may simply be acting in an environment with very weak selection pressures - they can do what they want because there are no natural threats to its organism. After a while that leads to evolutionary drift - in which the fitness of the organization no longer is determined by the environment or competitors, but simply generated randomly - and when selection pressure increases the organization collapses fast.

The best organizations exist in environments with intense selection pressures - because selection pressure generates micro-defeats all the time, and those educate, direct adaptation and helps you build a more efficient and resilient organization.

This could be an interesting observation when we look at the tech industry today. The first wave of consumer technology companies have succeeded relentlessly, stacking victories on victories in an unparalleled growth trajectory - two decades of growth and successes have now led to a culmination point. There is certainly selection pressures - but maybe they exist mostly at the edges of the companies’ core businesses? All of the large tech companies compete - and saying that there is no competition in tech is ridiculous - but you could they compete at the edges, leading to a situation where they are under only weak selection pressure - still able to add victories to their record.

The second generation regulated tech companies exist in a differente environment with an already high level of initial regulatory selection pressures, and intense competition between a multitude of different companies all competing in the same space. There is a center of gravity in, say, FinTech around payments where a lot of companies are competing for the same resources and looking for adaptations to help them do so. There is competition at the core of the market, and when we discuss competition we need to understand where it exists. Competing around a center of gravity is different than competing at the edges of other companies centers of gravity.

It is not obvious that one form of competition is better than another for society at large or the economy, by the way. But it seems obvious that for the company itself, the risks of competition at the edges are Luttwakian: a company risks thinking it is brilliant.

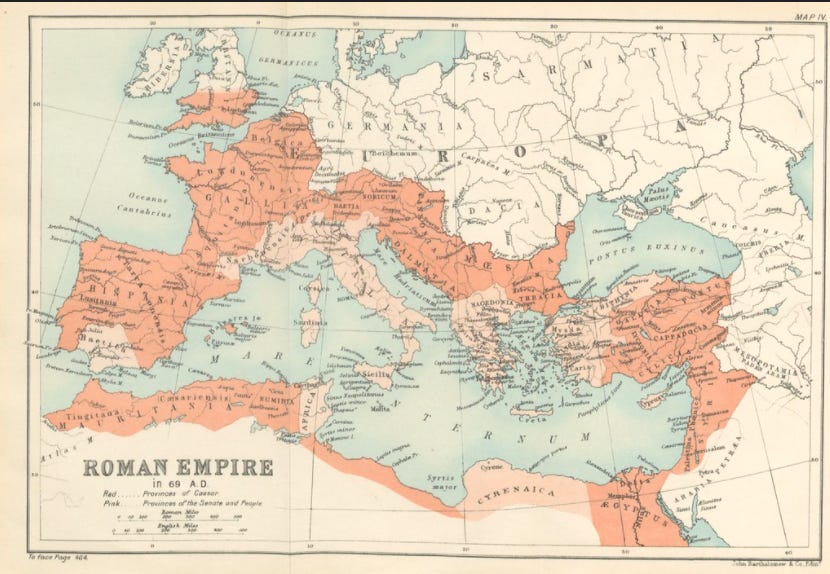

Back to our culminating point of success. If succeeding beyond this point leads to defeat, the reasonable next question would be what a company is meant to do at this point. Should it stop growing? Should it dissolve and declare ”mission accomplished”? It seems as if the analogy we have been exploring breaks down at this point: an army can dissolve or simply declare that they have won (Luttwak argues that the best generals have done this) and then not extend further. The victory then becomes a political problem - how do you create stability in a victory? Again, paradoxically, it seems as if the answer may be by weakening the victory as much as possible: the Romans were often thought of as great victors - they did not punish the conquered, let them keep their autonomy and often just put token Roman control in - creating a weakly linked but surprisingly powerful empire through a string of strong military victories turned into weak political institutions. Alexander the Great had similar policies - and the overall impression from history is that the best empires are weakly linked - and any attempt to build strong links usually led to uprisings or collapse.

But what could this possibly mean for a company? Can a company turn victories and turn them into weakly linked corporate empires? Perhaps. One could argue that we will see more and more corporations mimic the Berkshire Hathaway structure that Warren Buffett has built (which comes curiously close to a weakly linked empire). This will require ownership re-structuring and a lot of work to find out what the right weak institutions are, but ultimately the successful company would then evolve into a conglomerate - and then be subject to other kinds of failure. If we study old and aging companies we can find a few intriguing examples like General Electric, but it is not obvious that we can generalize from those examples - and perhaps we should just admit that our analogy runs into problems here. But it is worth thinking through. The recent move of Facebook to turn into Meta is intriguing in this perspective, as was, obviously, the creation of Alphabet.

So what?

The study of strategy is difficult, and military strategy is not wholly translatable to corporate strategy or political strategy - but there are partial analogies and lessons that we can apply. As we look at expert strategists like Clausewitz, von Moltke and Luttwak we can find mental models and tools that help us think creatively about our own strategic challenges. The two Luttwak-models here at least give us a few interesting ideas about things we can do.

First, study regularities. Political patterns, organizational patterns - your own and others. No analysis is complete without a sense of the underlying patterns and the historical regularities in reacting and acting around an issue. Your own regularities suggest vulnerabilities and areas of improvements. Others suggest possible points of maximum effective interventions. And while there are a lot of patterns, classifying and thinking through them is still worthwhile - because there are fewer than we think! If you want to apply this to your own life you will find regularities and habits that are surprisingly clear as well.

Second, explore your successes to find your future failures. And in tech - look at your technological victories to find future regulatory defeats. It will not always be the case that your technology sets you up for regulatory reactions, but it will be true often enough for the study to be interesting to undertake. And this is not just an organizational question, it may actually even apply to your own personal successes, and the defeats you have suffered.

Third, study the limits of analogies and where they break down. Analogies can be overly successful too — leading you to think that they carry more helpful guidance than they really do. Overextending analogies leads to defeat as surely as any other overextension.

As always, thank you for reading and keep sending comments and ideas for other notes! And do send the newsletter on - the more we are the merrier!

Nicklas