Unpredictable Patterns #148: AI and insurance

Risk allocation, the predictive turn and the cost of being predictably unlucky

Dear reader!

This week’s note is a discussion about how we deal with, price and allocate risk - and why insurance as we know it may not survive the predictive turn in society. Enjoy!

Allocating risk

All technology comes with risks of different kinds, and an important component part of the diffusion of technology in society is the emergence of an allocation of that risk over different parties. Often when we think about this we think about it as a question of liability - but that is just the first step in the allocation of risk; when we determine liability we set the default allocation of risk - but risk can then be re-allocated in different ways and through different mechanisms.

One simple mechanism is contract - we can agree that you take on a certain risk that I may have been allocated, or we can use contract to clarify which uses of the technology we recognize are so beyond the original allocation of risk that they create entirely new risks. Now, the legislator may, of course, explicitly stop me from doing that and assign me a non-transferrable liability for the technology - but even so there are often new, aggregate risks that have to be dealt with.

Insurance is another mechanism that can deal with risk in different ways. When I insure against risk I accept that I will be liable, but I buy an insurance that will allow me to recoup any loss my liability causes me to incur.

Now, insurance is fascinating.

Insurance, as a means of re-allocation of risk, traces its origins to ancient civilizations where merchants sought protection against the risks of trade. Babylonian traders around 1750 BCE developed early risk-sharing arrangements codified in the Code of Hammurabi, which allowed merchants to pay lenders an additional sum to cancel loans if shipments were lost. Similar practices emerged in ancient China, where traders distributed goods across multiple vessels to minimize catastrophic loss. The Greeks and Romans formalized burial clubs that collected contributions to cover members’ funeral expenses—an early form of life insurance. These arrangements shared the fundamental insurance principle: spreading risk across a group so that no single party bears the full burden of misfortune.

Insurance works if risks can be pulverized.

Modern insurance emerged in the commercial centers of medieval and Renaissance Europe. Maritime insurance developed in the Italian city-states during the 14th century, with Genoa producing the oldest known insurance contract in 1347. London’s Lloyd’s Coffee House became the epicenter of marine insurance in the late 17th century, where merchants, shipowners, and underwriters gathered to negotiate coverage for voyages. The Great Fire of London in 1666, which destroyed over 13,000 houses, demonstrated the need for fire insurance and led to the establishment of the first fire insurance companies. Life insurance also took more structured form during this period, with actuarial science emerging in the 18th century when mathematicians like Edmond Halley developed mortality tables that allowed for more precise pricing of risk.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw insurance expand dramatically in scope and sophistication. Industrialization created new categories of risk—workplace accidents, product liability, automobile collisions—that spawned corresponding insurance products. Governments entered the field with social insurance programs: Germany pioneered compulsory health and accident insurance in the 1880s under Bismarck, and most developed nations eventually adopted some form of public insurance for unemployment, disability, and old age. Today insurance is a multi-trillion dollar global industry encompassing everything from crop failures to cyber attacks, underpinned by complex financial instruments and reinsurance markets that distribute risk across the world economy.

AI and insurance

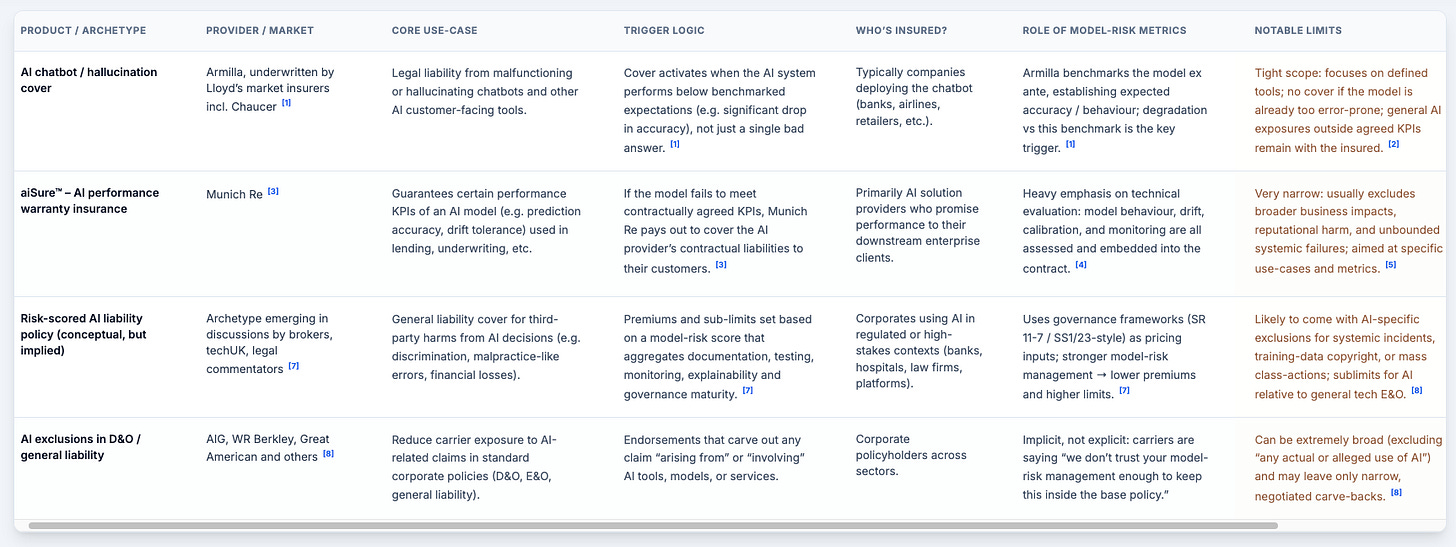

Lloyd’s of London and Munich Re have begun offering targeted, performance-linked coverage specifically for AI systems, while at the same time major carriers like AIG, Great American, and WR Berkley are racing to exclude AI from their standard policies entirely. This bifurcation—specialty insurers entering the space with narrow, data-driven products while generalist carriers flee—tells us something important about how the market is reading AI’s risk profile. The insurance industry is treating AI as a candidate systemic risk, comparable to cyber or certain exotic financial instruments.

The products themselves reveal a maturing understanding of what AI risk actually looks like. In May 2025, Lloyd’s market insurers began selling a product designed by Armilla, a YC-backed startup, to cover legal fees and damages when AI chatbots malfunction or hallucinate. What’s notable is the trigger logic: coverage activates not when a single bad answer causes harm, but when measurable performance degradation occurs—accuracy dropping from 95% to 85% over time, for instance, against a benchmark Armilla establishes upfront. Munich Re’s aiSure product takes a similar approach for AI providers, insuring them against losses if their models fail to meet contractually guaranteed KPIs around prediction error, data drift, or behavioural deviation. In both cases, the insurer is essentially backstopping model performance, which means they have a direct financial interest in how well the AI actually works.

The governance implications here are substantial. For the first time, model-risk practices—testing, documentation, monitoring, audit trails—don’t just impress regulators or satisfy compliance checklists. They move insurance premiums, giving boards a quantifiable financial incentive for AI safety and governance. A widely cited techUK analysis this year makes the connection explicit: firms with strong model-risk management, following frameworks like SR 11-7 or the PRA’s SS1/23, can expect to earn lower premiums. This couples AI assurance directly to AI insurance, creating an external price signal for governance maturity. Meanwhile, the carriers filing exclusions are implicitly saying something different: we don’t trust your model-risk management enough to keep AI inside the base policy.

What emerges could well be a new infrastructure layer for AI safety, analogous to what cyber insurance became in the 2000s. Brokers, reinsurers, and specialty carriers now sit between AI providers and end-users, making judgments about what counts as acceptable AI deployment. The current product landscape includes narrow chatbot liability covers, performance warranty insurance for specific use-cases, and—still conceptual but clearly foreshadowed—risk-scored general liability policies where premiums reflect governance maturity scores. The market is fragmenting along predictable lines: companies with documented, well-tested, explainable models will find coverage; those with opaque systems and minimal oversight will face exclusions or prohibitive pricing. Overall, the insurance models - if they work - will accelerate diffusion of the technology.

Project this forward five years and the following scenario becomes interesting. Through 2025 and 2026, the niche covers from Lloyd’s and Munich Re grow modestly, adopted primarily by digital-first companies that have already experienced AI incidents firsthand. Big carriers continue pushing AI risk out via exclusions, and corporate risk officers begin to recognise that their “AI gap” is as real as the cyber gap they scrambled to close a decade ago. By 2027 or 2028, a small ecosystem of AI risk-rating agencies and audit firms will likely emerge, offering standardised scores based on model documentation, testing, red-teaming, and monitoring—essentially operationalising what regulators and industry bodies have been hinting at. At least one major jurisdiction, probably the EU, UK, or Singapore, will start referencing insurance and independent testing in AI supervision guidance, making insurability a proxy indicator of acceptable risk or a presumption of strict liability if it is missing.

By 2030, for large enterprises in regulated sectors—banks, insurers, hospitals, critical infrastructure operators—AI liability and performance insurance becomes something close to a requirement for high-impact deployments, whether through contractual obligation or supervisory expectation. Premium differentials widen dramatically: an organisation with mature AI governance and explainable, well-tested models pays baseline rates, while one with opaque, minimally tested systems pays three to five times more or finds itself uninsurable at any meaningful limit. Corporate boards start receiving AI risk and insurability dashboards alongside their cyber and climate reports, and failing to maintain insurability for critical AI systems becomes a governance red flag.

The politics of AI risk will, in this scenario, increasingly run through insurance channels. Civil society and regulators will push for transparency on who is insuring large frontier models and on what terms. Systemic AI incidents—a catastrophic medical misdiagnosis cascade, a large-scale trading error—will generate high-profile coverage disputes that could shape case law. By the end of the decade, “model-risk score” could be a standard metric on risk committee agendas, much like Value at Risk in finance or security ratings in cyber. Insurance pricing will have quietly become one of the strongest external incentives for robust AI governance, and regulators will follow the money.

But there is another possible scenario here as well — and that is that AI essentially becomes uninsurable because exactly of those systemic risks that we pointed to above, risks that cannot be pulverized across many because they are likely to present all at once, say, or in cascading patterns, like dominoes.

If we come to 2030 and there is no insurance market for AI at all - if the rush to exclude AI became the essential trend - then a natural consequence of this will be slower diffusion and greater hesitance to deploy AI in fields like energy, health or finance. What we might see, however, is technology companies stepping in and self-insuring in this case, and so using their balance sheets to try to pulverize different kinds of risks that way — a shift in the sectoral logic that would have long-reaching implications.

The great exception will be the military, a sector of society traditionally not engaged or embedded in insurance practices at all (or at least not in the financial kind) - and without market discipline, AI-safety here will have to be developed by other means.

AI in insurance

There is a certain reflexivity worth noting here. We have been discussing how insurance might allocate the risks that AI creates, but AI is simultaneously transforming how insurance itself operates. The same capabilities that make AI a novel risk category—pattern recognition at scale, prediction from high-dimensional data, autonomous decision-making—are being deployed to reshape underwriting, claims processing, and the logic of risk pooling.

The most consequential shift may be in the granularity of risk assessment. Traditional insurance works by grouping broadly similar risks together and charging everyone in the pool a price based on aggregate experience. AI enables insurers to move toward individualised pricing based on far more variables than any human underwriter could process. Your car insurance can now reflect not just your age and postcode but your actual driving behaviour, measured continuously. Your health insurance could, in principle, incorporate genomic data, wearable metrics, and purchasing patterns. This represents a fundamental tension at the heart of the insurance mechanism. Insurance has always been, at its core, a solidarity technology—a way of spreading misfortune across a community so that no one is ruined by bad luck. The more precisely you can predict who will suffer losses, the more insurance starts to resemble simple prepayment by those who will need it, which undermines the pooling logic entirely. AI-driven underwriting pushes toward a world where the lucky pay very little and the unlucky become uninsurable.

This is not a new tension—actuarial science has been refining risk categories for centuries—but AI accelerates it dramatically. And it connects back to our earlier discussion of AI’s own insurability. If AI systems enable insurers to identify and exclude bad risks with unprecedented precision, and if AI deployments themselves prove too correlated and systemic to insure through traditional pooling, we may be witnessing a broader transformation in how societies allocate technological risk. The insurance mechanism, so successful at absorbing the risks of maritime trade, industrialisation, and the automobile, may need to evolve again—or we may need to think more seriously about which risks require public backstops rather than private markets. The allocation of AI risk, it turns out, is not just a question about AI and its dangers - it is a question about the future of risk allocation itself.

On the other side of insurance

There is a logical terminus to AI-enhanced insurance that may not be insurance at all. If prediction becomes sufficiently powerful and data sufficiently comprehensive, the ex post logic of insurance—compensating for harm already suffered—gives way to something like continuous, individualised cost allocation in the present. Your genomic profile indicates elevated diabetes risk, so sugar costs you more. Your purchasing patterns suggest you’re on your twentieth pack of cigarettes this month, so the price rises sharply. Your social graph has shifted toward heavier drinkers, so your alcohol prices adjust accordingly.

Every transaction becomes an occasion for predicting what you will do with what you’re buying and what consequences will follow, with the expected future cost folded into the price you pay now. This is an economisation of fate, your probable future converted into a premium you pay before anything has happened.

What disappears in this transition is the solidarity logic that made insurance a distinctive social technology. Traditional insurance worked because of a certain productive ignorance: we knew that some ships would sink, some houses would burn, some people would fall ill, but we couldn’t know which ones, and so it made sense for everyone to contribute to a common pool that would support whoever drew the short straw. The mechanism expressed a recognition that misfortune could strike anyone and that pooling risk was both prudent and fair. Predictive pricing inverts this entirely. It says that misfortune is not random but knowable in advance, and those who will suffer it should bear the costs before the fact.

The predictably lucky pay little; the equally predictably unlucky face compounding disadvantage, priced out of behaviours that others enjoy cheaply. This is a shift from mutual aid under uncertainty to individualised cost allocation under greater certainty—and whether the world it produces is more efficient or more just is a question that the pricing mechanism itself cannot answer.

Thanks for reading,

Nicklas

This is such a sharp articulation of how the predictive turn fundamentaly reshapes the social contract beneath insurance. The shift from pooling uncertainty to pricing individual risk doesnt just change premiums, it erodes the solidarity that made the system work in the first place. Once insurers can see who's predictably unlucky, the whole moral logic collapses into somethign more like gambling than mutal aid.