Unpredictable Patterns #144: Revisiting the health of the public sphere

Contexts, tribes and the merit of less human conversations

Dear reader!

This week’s note is an essay is co-authored with Fredrik Erixon and continues the work he and I started in a previous essay on the health of the public sphere. In that essay we asked what characterized that health, and here we explore where the public sphere fails, and why. As always the essays are our private views only. Enjoy!

Where is the public sphere getting sick?

What is a healthy public sphere? In the abstract, most people in liberal democracies would think of it as one with a plurality of views and an inclusive culture while respecting a high standard of truth. And today, many would also add: a healthy public sphere is like the one we had in the past. Their impression is that our healthy past has been succeeded by an unhealthy present. And the obvious culprit is modern technology – or, especially, social media. They have made us lonely and angry, polarised the public debate to the breaking point, and allowed the public sphere to be infused by lies and manipulated propaganda.

Is this a good way of thinking about a healthy public sphere? We think not. In a previous essay, we argued that the public sphere – like life in general – will always be defined by parallel trends of health and unhealth. Efforts by governments and others to regulate the discourse of truth, or the squares where debates happen (e.g., platforms), in the spirit of restoring health are prone to failure. For those valuing the liberties in liberal democracies, these efforts also rest on awkward thought. We said that an important feature of liberal democracies is that they have institutions who are not part of executive government that are trusted and generally reduce suspiciousness in the public discourse. These institutions used to be the courts, media, and universities, but they are far less trusted today, partly because they have diverged from their own standards and methodologies for helping societies to operate within defined boundaries of truth and reasonable disagreements. Generally, we concluded, a good way of thinking about a healthy public square is to explore ways of managing unhealth – and especially suspiciousness.

Where are we getting sick?

The question we are now asking is more spatial and less about definitions of health and unhealth: where in the public square, or society, is there a problem with unhealth? Or to put it differently: where are we getting sick

Many people will have a ready-made answer: it’s on X (Twitter), Facebook, or other platforms where lies and falsehoods, “misinformation” and “disinformation”, spread like wildfire. Others may disagree, especially those on the political “new right”, and say that it is rather “old” media like public service broadcasters or old broadsheet “papers of record” that is the source of unhealth. Their response, which may extend to the universities, has become equally ready-made.

However, both attitudes are jaded and leave many questions unanswered. One missing important observation is that the public sphere has never been a monolithic space but always tiered and fragmented to serve different identities, pursuits, and patterns of behaviour. For the analytically minded, it is impossible to understand the public sphere if the assumption is monistic and the task is to discover or locate THE pursuit that defines the public sphere. It is likely wrong – and, with technological and societal change, increasingly wrong – to think about the public sphere as one pursuit or one effort, serving one democratic purpose. In the first place, to understand where we are getting sick in the public sphere we need to understand immaterial layers of human action in the public sphere.

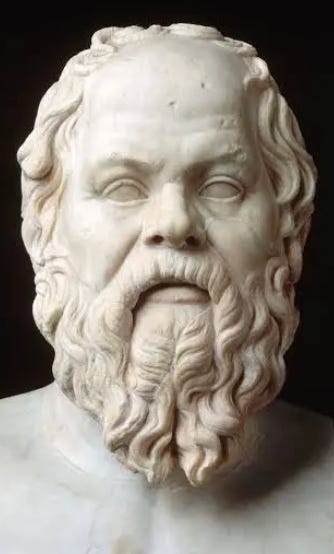

Anthropology and sociology can help to put some light on the issue. People have different patterns of actions depending on the task and the arena: there is even a difference in intentions. In Clifford Geertz’s classic work, The Interpretation of Culture, he argued that body and mind, reason and biology, sit alongside a distinctly human desire for living in systems of meanings. He said in a famous quote that “man is an animal suspended in webs of significance he himself has spun”, and this seems to be a good starting point for layering different contexts – or webs of significance – that have different pursuits and outcomes, and that operate under different rules.

We suspend certain aspects our biology, but the exact form of suspension depends on the web – and such webs are contexts that we need to understand in more detail. Moreover, people resolve frictions and disputes in different ways depending on the context: people are generally good at pragmatic negotiation with others if they are clear about the context and what mechanisms that culture and norms prescribe for constructive resolution. What are these webs or contexts? One way to divide them up is the following.

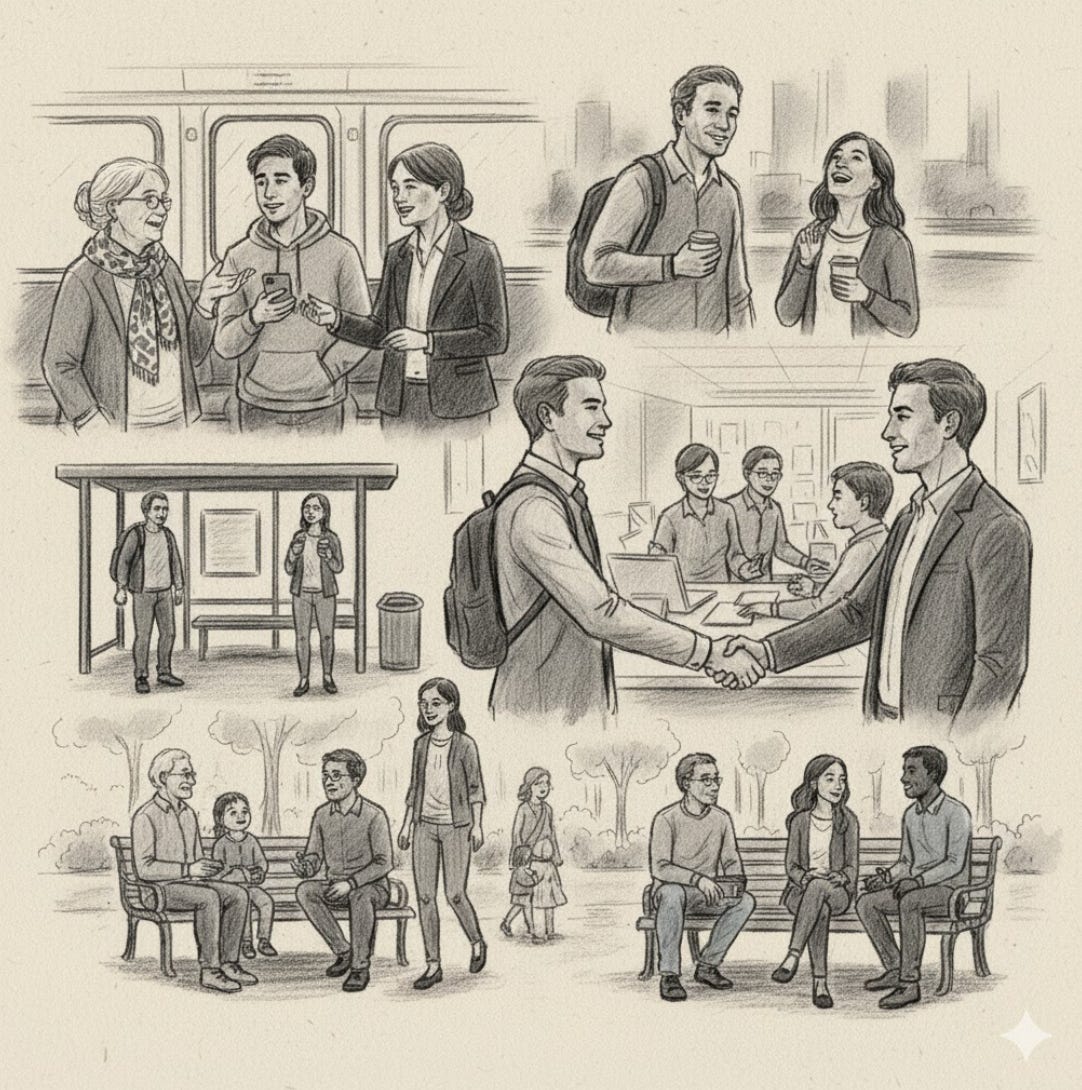

Private contexts

We all interact with lots of people that think differently from us. In most instances, very few have any problems with most of our encounters. We move together with other people in so many parts of our life without having issues with understanding each other. We follow established behavioural norms and, in most cases, refrain from thinking that another person’s political viewpoints are imperative for the encounter to happen or continue. Almost everyone can chat to someone about sports or the weather or daily events on a tube or at a bus stop in agreeable terms. Most people interact with colleagues at their workplace based on getting things to work smoothly and for people to be able to conduct themselves with satisfaction and efficiency. These skills are usually inter-personal, intergenerational, and international. It is notable how many of the private contexts are free from all the faults of a polarised society.

These actions and interactions are agreeable and non-polarising because they are essentially about coordination. In fact, a lot of human interaction is about coordination: material and task coordination, for instance. Obviously, we engage in symbolic coordination of different moments: talking to a stranger in public transport gives some form of meaning to the moment and coordinates an experience. Private contexts involve a variety of physical spaces and many different pursuits: they have in common that they help people moving together as a group, and – ideally – getting better at it.

Notable is also the existence of clear conflict resolution mechanisms in most private contexts. In the workplace, or in other private contexts, we know how to solve our conflicts – and we are incentivized to solve them because we are coordinating for a common cause of some kind. This will turn out to be surprisingly important as we discuss why other contexts are getting ill.

Tribal contexts

Some contexts have become primarily about expressing our identity and signalling various types of loyalties: to ideas, habits, groups, viewpoints, et cetera. The significance of this context lies not in the orientation towards coordination but to symbols and statements of meaning – sometimes by offering quasi-religious places of worship or the warm comfort of the tribe. It is a context that operates under certain norms and rules, and they generally work pretty well as long as interactors stay in this domain and, sometimes, in their lane. People can have significant disagreements with each other at the workplace, but as long as the interaction stays at the workplace problems are usually manageable – since we have access to clear conflict resolution mechanisms. Disagree? Well, ask a manager! However, if one person in a disagreement takes to X and posts about an idiotic colleague or a toxic workplace culture the interaction immediately enters another context. It gets charged not just by identity but differences over identity and why these differences matter. This is an example of a context violation – we push an interaction from one context to another, and when we do we change the terms of engagement and the conditions for resolving the problem.

Our tribal contexts have re-expanded over many decades. Obviously, social media plays a role: X, Facebook, and others created new contexts for identity signalling. But the re-expansion of this context started a lot earlier – and was clearly visible in mainstream media long before social media arrived. Different observers will point to different causes or indications for change. For some it is about celebrity culture, reality TV, and the personalisation of the public space that followed the expansion of mass media. Others may say that it is rather the result of deeper trends of individualism and new forms of social ascription that came with a declining role for traditional non-public spaces of identity – family and churches, for instance. It is notable, though, that many of the concerns that fuel the debate over social media are copies of concerns that previously have featured in similar debates. Pierre Bourdieu and Christopher Lasch are both thinkers that are referenced by critics of social media. But Bourdieu, who died in 2002, was predominantly occupied by vacuous entertainment media. Lasch’s most important book for the current criticism of social media was published in the 1970s. The year he died, Mark Zuckerberg turned ten years old.

Tribal contexts are the remnants of idealized democratic contexts – the idea that there is a single public sphere in which we engage as citizens in seeking out consensus through debate. As societies grew more complex, this public sphere fragmented into contexts oriented – primarily – around identity. This has nothing to do with social media, but with the fundamental complexity of modern society – a society in which the idea that there is a single on-going public conversation simply is an illusion.

The dominant method of conflict resolution in this context is simple: it is choosing which tribe you belong too, and then conforming to the positions taken by that tribe.

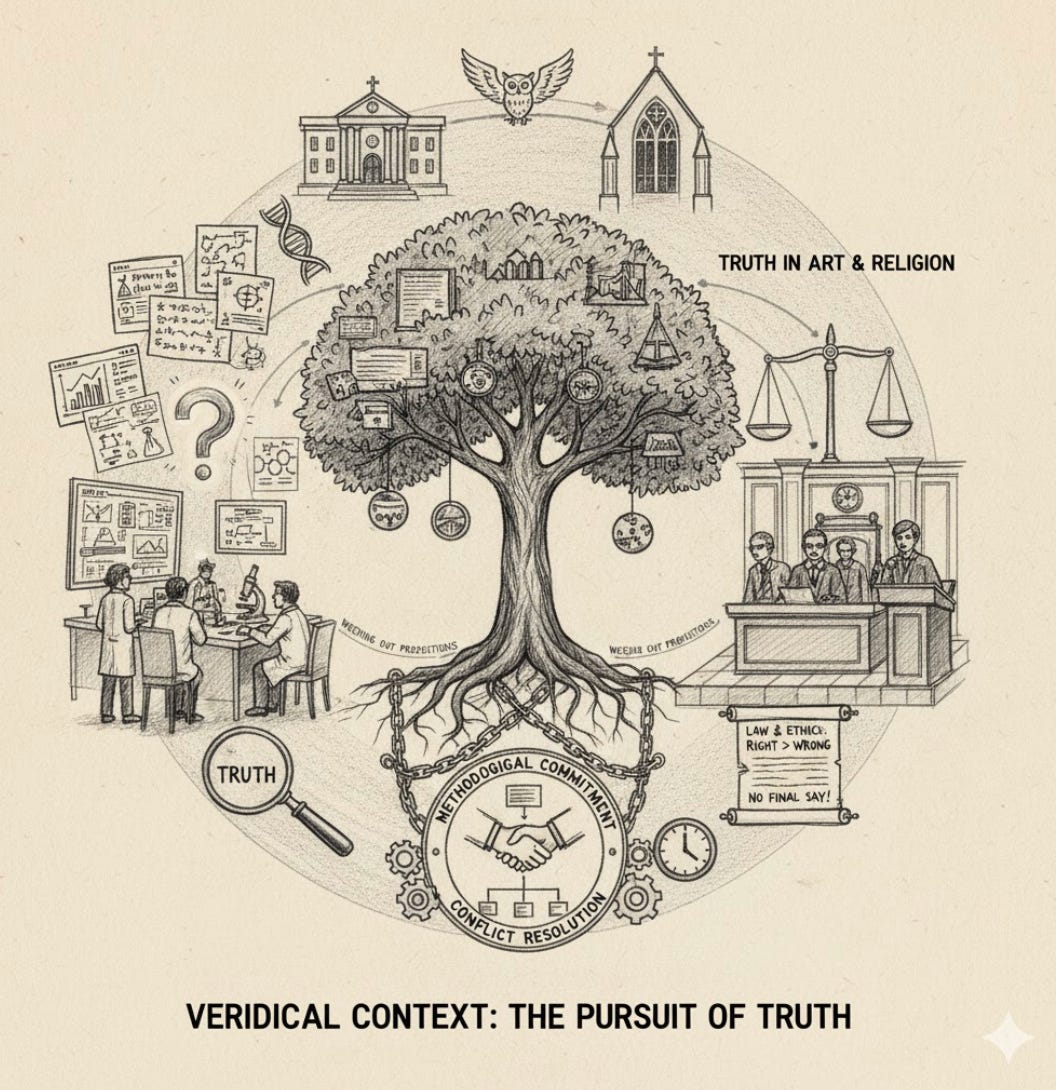

Veridicial contexts

Lastly, there is a specialized, and highly important veridical context – a web that is significant because it basically involves questions about truth. In short, this is a context for broad or narrow truth-seeking enterprises. This involves the world of science: scientific truths and the validity of scientific claims are an important part of it. However, truth can also be about non-science issues. For instance, it can be about truth in art or truth and religion, and it can extend to issues of law and ethics, about what is right or wrong. The rules here eschew fixed and final views – the basic rule is: no one has a final say! – but they lead to norms and standards for the truth-seeking enterprise. The veridical context is a context with an ethos and methods of weeding out propositions and evidence that do not stand up to scrutiny. Therefore, it is not a place just for universities and scholars: it may even be that, in some academic disciplines, their adherence to this context has weakened over time and shifted into tribal modes. It is also in this context we find other important institutions like courts

The key thing about this context is that it has institutionalized mechanisms of conflict resolution and people committed to adhering to them. Here conflicts are not solved by authority – asking the boss – or by tribal assertions of loyalty, but by a methodological commitment of some kind, and a belief in that method of conflict resolution.

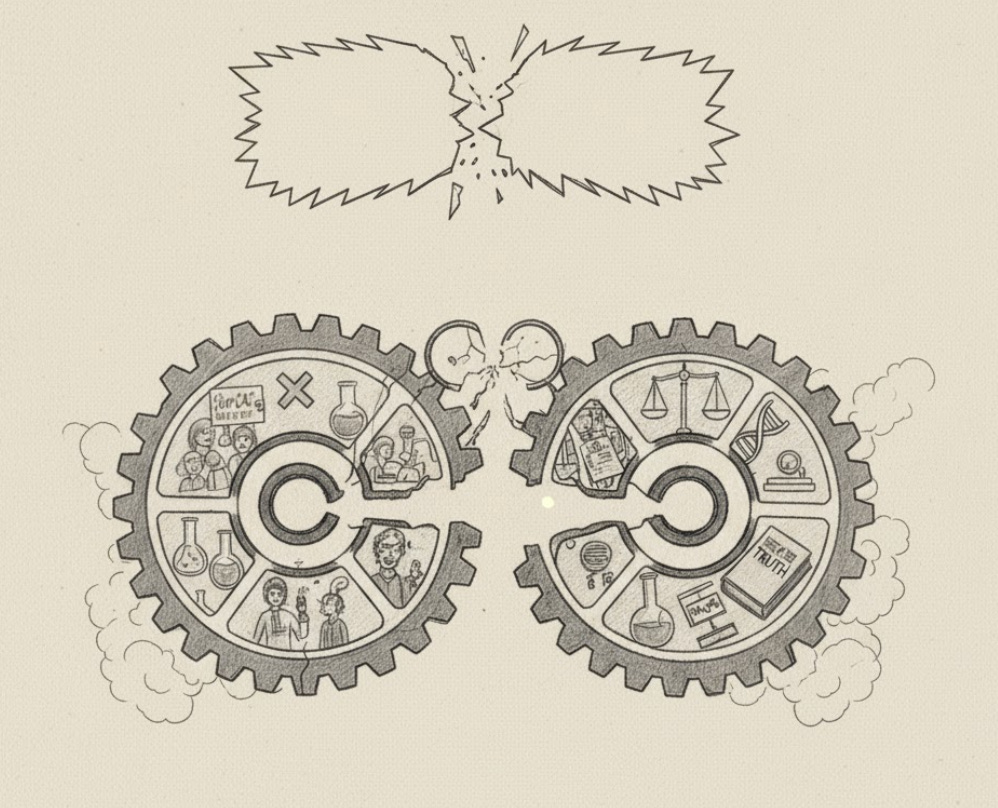

Context violations

So where do these layers take us in our quest to understand where the public sphere is getting sick? In most societies, people act across all these contexts, even if there is a lot of individual variety. People also cross contexts while understanding that there are clear – yes, sometimes rigid – boundaries between them. This has been the practices for a long time: what distinguish humans is that the quickly learn and adjust to what rules that apply to certain contexts. Nor does it seem to be a major problem that people have conflicting identities or that they debate them within a context. This has always been the case in modern life. Actually, it is difficult to contend that the major problem with polarisation is that people have different political identities and that they use tribal contexts for identity signalling.

A more plausible thesis is that we are getting sick when contexts mix – or when different webs of significance get interwoven in ways that blur conflict resolution mechanisms. In other words, it is when contexts crash together that the health of the public sphere is weakened. These points of conflict are the areas of disease risk. Context violations are principally frequent in periods of strong political conflicts – they may even be one of the causes of discord. For instance, the revolutions of the 1960s in sex, music, clothes, and mores featured strong context violations between private and tribal contexts: it was a “conflict of generations” within families as much as in the public sphere.

We have a similar experience today with context violations – yet this time they are principally taking place between the tribal and veridical contexts. The debate about vaccines is a case in point. What is the best way of understanding the voices, people, and leaders that have given rise to an anti-vax mentality? In the first place, very few of them are active in the veridical contexts – seeking truth. The public spere generally features a lot of identity signalling about health, exercises, food, and the use of pharmaceuticals, and voices in that antivax or vaccine-sceptic space are often signalling a broad identity. The lion share of them is not really contesting science in a substantive way – say, having an evidence-based discussion about the germ theory of disease, and if it is true or not. Scientific arguments against their position do not land well because those signalling identity are engaged in a different enterprise. A notable part of anti-vaxxers rather seem to think they are making a statement against, for example, ultra-processed foods and chemicals in food. Others are signalling an identity based on family grief and suffering over unexplained and taxing neuropsychiatric disorders. A third group still rather seem to signal that they are open-minded people with a big spiritual vista: they are intellectually flexible rather than rigid. Very few of them are saying: “sure, call me a fool if you like when I am dismissing basic medical microbiology, but I know that I am right and that medical experts are wrong, and I have the evidence to prove it!”

They do not commit to any established, institutional method for resolving conflicts of evidence – but seem to deny that such methods are viable ways of deciding conflicts at all.

A context violation becomes inevitable for several reasons. The first, obviously, is because many anti-vaxxers are challenging medical expertise: they step over the boundary. These may not be veridical claims but a common accusation is that medical experts are frauds and/or have been corrupted by industry: they are paid to help companies sell their vaccines. The sceptics challenge the ethics of the scientific pursuit leading up to vaccines, or the recommendation of their use. They call into question the integrity of scholarship and the methods of conflict resolution in the veridical context.

A second context violation is that their opponents in the tribal context also cross into the veridical context to borrow authority for their identity. They are not inviting a discussion based on the rules that govern truth-seeking; many of them rather want to signal that they are enlightened, responsible, and part of the culture of science. Obviously, the real medical expertise must respond, too, because the avoidance of vaccines is a matter of life and death. However, the rebuttals of the experts are not having much impact on the vaccines-sceptics because they are responding within a conflict resolution mechanism not recognized by the opponents. Meaningful discussion is difficult without agreed conflict resolution mechanisms.

In this view, the health or unhealth of the public sphere in matters of vaccines have little to do with public knowledge. The share of the population with an informed understanding of microbiology and vaccines have likely not changed very much in the past, say, 30 years. The change in the public sphere is better understood as one of identity and webs of significance – and in choice of context in which we debate vaccines. Back then, it was more common that people expressed an identity with trust in authority. However, it was also more common that matters of vaccines, medicines, health, and food were discussed in private contexts. The domain coordinated knowledge, community, life, and family and did not involve making public statements. Boundary restrictions were more respected and, as a result, the public sphere was healthier.

On other issues, context violations are happening by the veridical context expanding into the tribal. Many scholars, scientists and other engaged in solid scholarship are careful about public communication and avoid expressing over-confidence in their own knowledge about truth. For them, science is a pursuit, a method, a truth-seeking process. However, an increasing number of academics have stepped over boundaries and cloaked identity-signalling in the banner of science and truth. As a result, context violations happen and the public sphere gets sick because, in debates over identity, one party say – rightly or wrongly – that they are allied with the truth. In fact, it is notable how many of the major debates in recent years have featured such context violations: debates over climate change and immigration, for instance, or gender and sex invariably include claims of truth and lies, right and wrong, virtuous and unethical thought. But rarely any commitment to an agreed mechanism for determining which side is right.

Most Western countries had a strong touch of such context violations during the Covid-19 pandemic: it was a festival of identity-signalling using science and propositions of truth to bully opponents. In the UK, debates over Brexit (was it good or bad? Was it based on truthd or lies? was it real or fake Brexit?) still end up in strong identity signalling – again without clear commitments to any method or process to resolve the conflict.

Is there a technological cure?

Technology and social media have played a role in expanding the tribal context: for our stone-age brain, social media can be like a hall of mirrors for narcissists. Social media is tribal infrastructure. However, it is equally clear that social media is not the bogeyman it is often presented to be. For instance, there is not much evidence suggesting that Russian bots and social media campaigns have swayed many voters in elections. Likewise, there is next to no evidence suggesting that people of moderate views are persuaded by extreme content to change their views. In fact, a good amount of research suggest that social media plays a negligible part in provoking polarisation, tribalism, extreme views, and other symptoms of unhealth in the public sphere commonly associated with social media. For sure, social media, algorithms, and recommendation systems can create echo chambers for some, but they also serve up contradicting thought – at a rate that did not exist in the past when choices of media consumption were more biased. If we are looking for more distinct places of unhealth in the public sphere, we need to sharpen the analysis.

One explanation to the insignificant effect of social media on the symptoms is that algorithms are not as powerful as they are billed to be. Just like social media has a lot of “dumb” advertising (tailored ads you are just not interested in) algorithms are not capable of serving us what we want at a certain point in time. Humans are creatures of variation and feelings: the tunes you listened to one morning are necessarily not the same tunes you want to listen to the next morning, let alone that evening. For most people, their politics tend to be all over the place, and just because you have eye-balled two clips about the nutrition standards of energy drinks on TikTok, for instance, doesn’t mean you are interested in a third, fourth, or fifth clip.

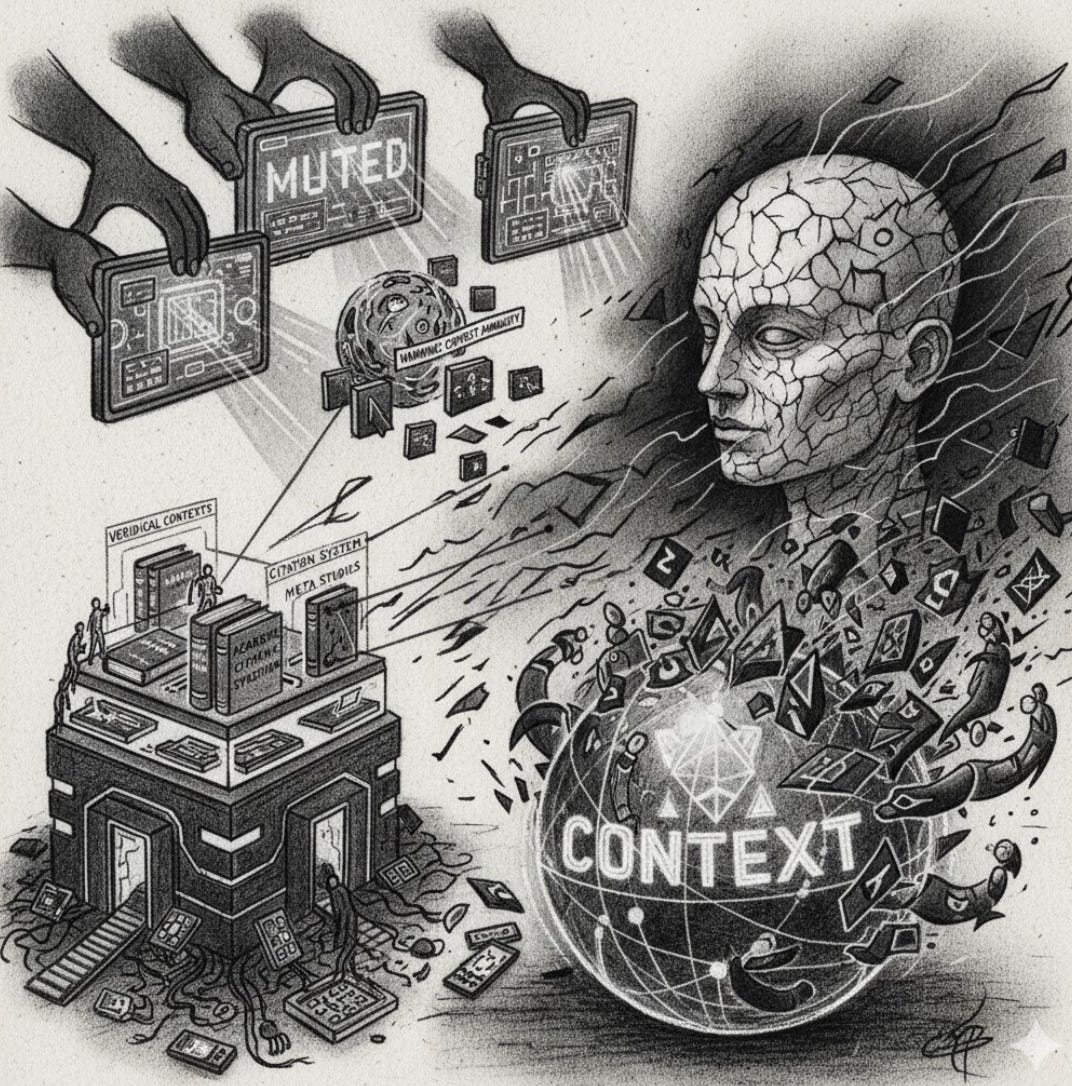

But what if we flip the debate: can there be technological cures to unhealth in the public sphere, perhaps some that help managing context violations? In fact, there have been many attempts exploring what happens in and between contexts. Obviously, social media companies have made several efforts to manage the health of the public sphere by muting certain posts and adding warnings to others that they sit awkwardly with bodies of established facts. Many specialised platforms have strived to increase public access to veridical contexts. Academic publishing sites, citation systems, the use of meta studies are all attempts to both make contexts more distinct and supply conflict resolution mechanisms. However, most efforts have failed to achieve much for the health of the public sphere or for managing context violations.

Wikipedia is an interesting example. It builds on an old idea of the encyclopaedia, a summary of all relevant knowledge baked into a book of truths. In Denis Diderot’s view, the encyclopaedia is a way to democratise knowledge and change the way people think. Diderot’s view is interesting: it combines a top-down concept of truth (after all, he, d’Alembert and others were supposed to select the anointed truths) with a bottom-up idea of diffused knowledge. The basic notion was that if we can change the way people think, we can change how they think of themselves and how they behave. Wikipedia started with the same idea just as Google defined its mission to organise all relevant information and make it accessible. Wikipedia, however, established a method for developing content which was based on decentralised human contributions and validations. Unlike Google, which used algorithms to catalogue information, Wikipedia aspired higher: its method would turn information into knowledge – make diamonds out of carbon. And – perhaps most importantly – it built an informal, grassroots conflict resolution mechanisms in between editors that expanded into an institution.

Unfortunately, Wikipedia’s model has become contested – not just by right-wing voices but also by others, even by some who helped to found it. It has been accused of various biases and as Wikipedia is also source material for AI models, the risk is that biases will proliferate as the use of Wikipedia will gradually be taken over by AI agents. While Wikipedia sits in the veridicial context – it reports knowledge, ideally valorised knowledge – it has not been able to defend against an encroaching tribal context. And yes, it is the context violations that have caused frictions and prompted critique. Elon Musk now says xAI is going to launch its own Grokipedia – and his supporters are not blushing when they claim this new repository of knowledge to be a source of “true knowledge” – but without the conflict resolution mechanism, solidly signalling that this is a tribal technology.

An alternative approach is perhaps to discard the monistic concept of an encyclopaedia with valorised truths alone and look at more specific services that concern boundary conditions of contexts – and, perhaps, the rules of engagement between them. For example, one approach could be to combine a Wikipedia-style structure with defined layers of reasonable disagreement and reasonable differences in interpretation of established bodies of knowledge. Neither the health of the public sphere nor the veridical context is helped by the notion that science or Wikipedia or Grokipedia present “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth”. Obviously, there are areas for basic reporting of knowledge. However, a great amount of reporting is also necessary for reasonable disagreements.

What is needed is the building of real, robust technologies of disagreement and conflict resolution that can connect contexts in ways that a majority accepts. How do we support reasonable disagreements, and build the infrastructure for it?

Such an approach start with ideas and scholarship by thinkers like Friedrich Hayek and John Rawls. Rawls especially explored the concept of reasonable disagreements and identified six good reasons for observing them: 1) when the evidence is complex and sometimes conflicting, 2) even under certain forms of agreements, people can disagree about the weight a specific consideration should be given, 3) many concepts we use as humans are ambiguous and can be undermined by specific evidence, 4) we cannot entirely dismiss our own experience when we assess evidence and put weights on specific pieces of knowledge, 5) if an issue is charged with opposing normative conclusions, it is difficult to provide an overall assessment, 6) many difficult decisions do not have an easy solution staring it in the face. This is a good starting point for understanding reasonable disagreements and, also, how context violations could be managed. Many of these violations do not include binary situations with one proposition that is obviously true and one that is obviously false: they usually operate in the space where disagreements are reasonable.

What we need is to support that space with tools and technologies that allow us to explore the disagreements more clearly, and agree on methods of resolving them – or recognizing them.

Wikipedia did work out methods for observing reasonable disagreements: it is partly reflected in its work, method, and output already. But the task extends far beyond Wikipedia and includes media (old and new), schools and universities, platforms, museums and theatres, government authorities, and others. Context violations are inevitable, but they can be managed a lot better if people are helped to understand what it is reasonable to disagree about.

Most likely, although this may seem controversial, they can be managed a lot better if they are organised by technology than by humans.

Let’s explore what we, somewhat grandly, could call aporetic AI. Imagine an AI-mediator that forced context violations into dialogues, and provided participants with the means to sort out what resolution mechanisms they have available to them. Guiding us through arguments and disagreement, providing alternative means of conflict resolution, such technology would open a space for engaging across contexts. This is not a new idea, of course. In fact, dialogues have always been the way to manage context problems and violations, and they help to reduce the the tribal context. The health of the public sphere is most likely going to improve if more issues could be brought into such a new dialogical context. If you make a strong claim and borrow veridicial authority for it, you should be prepared to accept a dialogue that help to structure a disagreement with relevant mechanisms of conflict resolution.

There is a broader observation here: may it be easier to have AI help us to resolve conflicts than trusting humans to achieve that result? In his famous essay An apology for Raymond Zebond, Montaigne asked if people are afraid of nature because it is non-human or all too human? The same approach is useful for understanding anxieties over technology, social media, and AI poisoning the public sphere. What we should be afraid of, perhaps, is not that AI is non-human but that efforts by man (e.g., regulators) can make it all too human.

The point of using AI to manage contexts is that is not signalling identity and avoids a feelings-based approach to truths. Therefore, it can be better prepared than humans to define contexts and allow for managing disagreements.

AI has already proven to be a good tool for using dialogue to reduce the belief in conspiracy theories – in theories, for instance, that the US election in 2020 was “stolen” or that Covid-19 restrictions in Germany had sinister origins. In a world where many more spaces are influenced by identity-signalling – schools and universities, theatres and museums, courts, old and new media – the best way to reduce unhealth in the public sphere is perhaps to invite everyone for a dialogue that is less human.

Fredik Erixon & Nicklas Berild Lundblad