Unpredictable Patterns #12: Agency, attention and accountability

Why "the Internet made me do it" damages the debate, Tolstoy and the attentional engines of art

Dear Reader,

I am back in Stockholm after a wonderful trip to the mountains. It is spring, I think, and the air is thin and the sun is returning. Vaccines are slow to be distributed in Sweden, but there is hope that we will get them before end of summer at least. The pandemic is by no means over, but there is some hope that it can soon be fading into the past, and then we need to start looking at what we learnt. It will be challenging both on a societal and individual level, I suspect. The echoes of the pandemic years may be long or short, and different for all of us, but for many generations this is the first time we share a crisis, and that will stay with us. I also think we will grow from it, change - in a lot of ways.

This week’s note is about change, in a way, individual change and agency. What we can and do choose to do with our time and attention.

The problem of akrasia

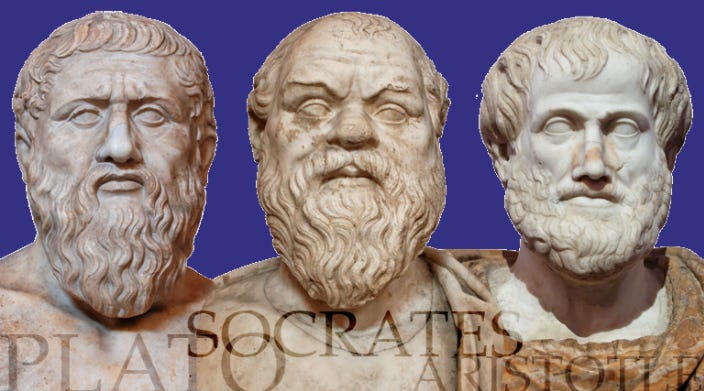

Here is what sounds like a really simple question: who is responsible for your actions? And here is another one: do you sometimes act against your own interests? These two questions circle around an old philosophical debate about what the greeks referred to as akrasia - something we could translate to, roughly, ”weakness of will”.

Socrates denied that there was such a thing at all. In the Protagoras Plato has him noting, almost in passing: ”“No one, who either knows or believes that there is another possible course of action, better than the one he is following, will ever continue on his present course” (/Protagoras/ 358b–c)”.

It is worthwhile to pause and note how revolutionary that statement is: what Socrates is saying is that if you act against your own interests it has to be because you are mistaken about the relative values of the different actions you are contemplating. Once you know the real value you will not hesitate, but choose the right action.

To act virtuously then becomes to know how things are and act accordingly.

Anyone who procrastinates, eats bad food or drinks too much is simply mistaken about the truth, and the best we can do is to help them realize that they are not valuing the actions available to them in the right way. Then, when they realize this, they will change their ways.

There is a cruelty in this view but also an almost absolute faith in human agency - and both are equally astonishing for anyone who suspects that human nature can actually really be weak.

Aristotle did not buy this, but suggested a much more nuanced view of human will and weakness. In the Nicomachean Ethics, he distinguishes between two different kinds of akrasia - asthenia and propeteia. The first is a weakness that abandons the rational choice found after deliberation in favor of a feeling or mood and the second is acting with out any deliberation at all.

Aristotle also makes another interesting observation - and that is that weakness of will is not accidental and temporary - it is usually a part of a pattern of action over time. We do not just succumb to weakness of will randomly, but the strength of our will is exhibited in the pattern of our actions over time - and so everyone of us has a level of willpower that changes continuously over time (and can be practiced and strengthened through the right measures).

In Aristotle we also find the two key passions that derail us: pleasure and anger. Pleasure - he suggests - is the bigger threat to our willpower, but anger also plays a significant part in us not acting in our interests.

What this suggests is that we have four different kinds of weakness of will to contend with: impetuous action inspired by anger or pleasure, or weak action where anger or pleasure undermines what we rationally know to be the right thing.

While Aristotle is much, well, kinder, than Plato here in granting that we can be derailed by our passions, it may not be so much a break with Plato as we could suspect, given that Plato actually believed in the three parts of the soul: the spirited part, the appetitive part and the rational part. The two former always undermine the third.

The big difference is that Socrates in Plato’s version seems to suggest that the rational part can always win if it is clear about what is right and in our interest, whereas Aristotle is more lenient with us and suggests that even knowing what is right may sometimes not be enough.

So, why is this interesting for us when we think about the Internet? And tech policy? I will argue that this problem lies at the heart of a lot of the tech lash and that if we do not address it we risk ending up solving the wrong problem.

”The Internet made me do it”

Much of the tech criticism that we see today is about how the design of technology tricks us into acting in certain ways. We scroll endlessly, we become enraged by the selection of content in the feed we consume, we succumb to groupthink because we encouraged to by the likes and hearts and comments on our social media posts. Our phones fragment our thinking and our screens slowly turn our lives into meaningless marathons of mediocre media shows. We vote for Brexit and Trump, and end up polarizing society.

This criticism is not new, just as the rhetorical structure of the tech lash is not new. We can find it with early technology critics like Neil Postman, in his Amusing Ourselves to Death:

”What George Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Aldous Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture … As Huxley remarked in /Brave New World Revisited,/the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny “failed to take into account man’s almost infinite appetite for distraction.”

Postman here frames the question as one of distraction, and the overall conceptual framework we encounter here is one in which technology and technology companies capture our attention and direct it in ways that do not benefit us.

All the criticism since - from Tim Wu over Tristan Harris and Shoshana Zuboff - merely offer variations on this theme: man is distracted by technology, his or her attention captured and the resultant choices are bad for us individually and collectively. It is worth quoting Tristan Harris on the subject:

”Technology has- intentionally, and through unintended consequences, manipulated human weakness. You can view most of the harms that we are now experiencing as rooted in this: addiction, distraction, mental health issues, depression, isolation, polarisation, conspiracy thinking, deep-fakes, virtual influencers, our inability to know what is and isn’t true….

Our past technologies, such as hammers, didn’t manipulate or influence our weaknesses… they didn’t have a business model dependent on building a voodoo doll of the hammer owner that allowed them to predict the hammer owner’s behaviour, showing them videos of home construction such that mean they use the hammer every day. A hammer is just sitting there patiently waiting to be used.

Technology is systematically undermining human weakness, the costs are huge. This is what degrades our quality of life and how we make sense of the world. This is what destroys our ability to form identity, to form relationships and make choices. This is what stops us from being able to make /decisions/ that can move towards solving climate change and dealing with injustices and inequality.”

Harris’s analysis is void of any human agency and he essentially argues that technology is not just distracting us, but actively making choices for us that are bad for us, replacing our will. Technology, in this criticism, has started to build astheneia in as a feature.

In this view we do not stand a chance, and the idea of individual responsibility is discarded almost immediately. Our agency has been consumed by technology and so the simplest versions of this criticism end up being crude versions that essentially amount to nothing more than saying that ”The Internet made me do it”.

There is a great temptation to accept this explanation, for several different reasons. The perhaps most important is that it does not forces us to look ourselves hard in the mirror, and ask what responsibility we have individually for how we use our technology. We can shift blame over to technology and so we do not have to have the harder discussion about our own moral responsibility.

It is a fundamental rule in political rhetoric that it is always better to blame things than people.

If you blame people, and ask them to be individually responsible for their choices, you are risking losing votes, so politics will always gravitate towards blaming things. It is notable that a lot of the criticism of technology companies is of the technology and the companies rather than the people building it or the leadership of those companies. There is some, to be sure, but it is far more common to speak of ”tech companies” than their CEOs or employees.

But this framing of the challenge undoubtedly are facing opens up the entirely wrong solution space. The question becomes how to design the technology differently, so that it induces different behaviors and encourages different sentiments. Instead of giving people back control over how they pay attention, the suggestion is that we need to distract citizens in a different way.

This leads incrementally to an acceptance of the thesis that it is the task of technologists and engineers to design behavior and encourage different virtues - it leads to the idea that we need akrasia-defeating design rather than individual freedom and control. If Harris’s criticism is that we have built technologies that are intentionally weakening our will, his solution is not a return to the hammer - but to build technology that shifts our intentions and shapes our will in a different way.

The answer to the machine, in this view, is in the machine.

Individual accountability

Let’s look at another possible way of framing the debate, and build it from the opposite of akrasia - enkrateia - the ability to act willfully and with intent, or with mastery over one’s own emotions. In this framing we would say that yes, there has always been distractions and they have always led to outcomes where we sometimes act in ways that are not in our individual interests. The citizens in Rome attending the fights in the Coliseum where distracted, just as we are.

Distraction is a known failure mode that civilization always operates in.

And the reality is that we seek distraction as a part of pleasure. There is a demand for distraction that has to do with the fact that we are imperfect beings, and we know it. We also know that we can do better, but see no reason to do so while there are things that we can blame for how we act. We will not take individual responsibility for our actions unless required to do so.

We will only build enkrateia if we are required to and held accountable for our own actions, and when it no longer is ok to blame things and circumstances for our actions. Agency and ownership require a certain social structure that is being undermined by the current narratives around individuals as victims of technologies.

We will only pay attention when we know that we will be held accountable for doing so.

In this framing we are agents, not victims. And we seek our own truths and decisions, and we do not have them imposed on us by well-intentioned designers who decide what is best for us.

We may be distracted, but if so we choose to and that choice is free and should be respected as such.

Such a framing, today, would be seen as extremely provocative - but is it really that wrong? And if it is, what degree of weakness should we assume that a population exhibits? The proponents of the tech lash theory are arguing, ironically, along the same lines as authoritarians: they are arguing that people do not know what is in their own best interests and that choices have to be made for them.

Underlying the tech lash, a proponent of this view would argue, is a contempt for individual agency disguised as concern for our well-being.

Here is the thing: if you assume that people have been lured into their current pattern of decision making by technologies, you have to assume that this weakness was there to begin with. The ”infinite appetite for distraction” is not induced by technology, but an inherent psychological trait in mankind. Removing the technology does not remove that weakness of will.

Blaming the technology does not solve the real problem of akrasia.

Our appetite for distraction

When we say that we have an appetite for distraction, that there is a demand for distraction, we are saying something that needs qualification. Being distracted is not just not paying attention - it can be paying attention in different ways.

In a recent book, C Thi Ngyuen suggests that we can learn a lot from studying why people play games - a known form of distraction. Games, he suggests, are an artform that sculpts agency. We are able to divide up our agency into tiers and enter a gaming mindset that allows us to play a game with full attention, while being distracted from everything else:

At the center of this picture is our capacity for submersion—for losing ourselves in a temporary agency, and momentarily blotting out our connection with our enduring values and ends. And I start to think about why it might be important for us to have this capacity, and how our ability to play games may relate to other practical needs and abilities we may have.

Nguyen, C. Thi. Games (Thinking Art) (p. 53). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

Distraction is not the absence of attention, but just another way for us to structure agency in to temporary and tiered forms of individual intention.

All art is, in this way, distraction. It allows us to redirect attention in new ways and is built - much as technology - to interact with our attention. And there is a parallel to the tech lash argumentative pattern in a lot of warnings about how music will destroy the youth or corrupt it, or how certain music can make us even kill or why there is such a thing as art that corrupts the purity of a culture.

Let’s take a really interesting example of this mindset. In Tolstoy’s Kreutzer sonata we find this argument - the argument that objects of art and fashion make us do things - in a number of versions. The protagonist argues forecfully that women’s dresses are made to arouse men’s desires, and that certain music can change a person’s mind to the point of homicidal rage or another’s to fall in forbidden love- and ends up killing his wife.

The Kreutzer sonata is a novella in which man is portrayed much in the same way as we are portrayed in the common tech lash criticism - as victims of passions, fully given over to impetuous anger and pleasure, directed by objects outside of our own volition.

Art is related to technology in a number of ways - both technology and art are artifacts that we interact with and as William Seely suggests in his excellent book Attentional Engines (Thinking Art) on the neuroscience of aesthetics, this tells us something about how we approach them:

”Artworks are artifacts, not natural kinds. Artifacts are, more often than not, tools created for a purpose. Their appearances are not the product of, and so not a clue to, an adaptive biological etiology. The appearances of artifacts are, rather, clues to their intended purpose or function. The etiology of tools is therefore social and psychological. It reflects a shared set of negotiated conventions for the ordinary uses of artifacts in familiar tasks.”

Suddenly we see that we need to make room for not just attention and distraction in our model, but also for intention and use. And with intention we come back to agency, and with agency we see the importance of accountability.

We would never accept a theory that said that a woman’s dress was designed to arouse a mans desires or that a sonata by Beethoven made us kill our spouse. Yet we seem curiously eager to accept Tristan Harris argument, and argument that rests on exactly the same kind of premises.

This only happens because when we talk about technology we tend to ignore intention and use. We intend to use technology, we choose to use it, in different ways, as Seely suggests, in negotiated conventions.

And this gives us some middle ground to explore.

We need not end up in Plato’s camp and suggest that we are undeniably responsible and accountable for everything we do with technology. We can look to negotiated convention of use for technology, and accept that we have to act intentionally and with accountability when we use technology. We are not victims of technology, just like men can never be victims of fashion designers or composers, but neither are we free to use technology in any which way we need.

It is the negotiation of social conventions and uses that determines the impact technology has on society and on us as individuals. Those conventions cannot be designed in or designed away - they can only be dealt with in how we use the technology and that is where the focus of our discussion needs to be.

So what?

This week’s note has been on the philosophical side, but I do think that it has some pretty direct implications for how we think about the tech lash.

The first is that we need to bring out the assumptions made by the current school of technology criticism really clearly - to show how they essentially start from the same argument that the man starts from who blames a woman’s dresses for his lusts - it may seem harsh, but there is very little difference in the structure of the argument (if you do not believe so read Harris’s quote above as a defense for redesigning women’s clothing - it actually does fit worryingly close - complete with a reference to better, earlier times when things were simpler). We need to return to the issue of agency, especially through the concept of intentional use. This is a move that is necessary to have any productive discussion about technology at all: without it we end up designing people out, not in.

The second is that we need to think more about the negotiation of social conventions for use, and look into how these negotiations can be opened up even more. That may actually have to do with technology - but not with technology that builds akrasia out, but technology that opens up for enkrateia - for not just individual choice but social negotiation.

The third is that we need to encourage the growth and deepening of social institutions that build on individual responsibility and accountability. Transparency into systems and data is one aspect of this, but more than that we need to teach people the negotiation of use early, in school - and there I am optimistic. I think children today use technology differently than us, and that they can - if they are not made out to be victims in our political discourse, negotiate very different and innovative conventions of use.

There are more things and I think there is much more to be said about the relation between intention, use and attention - but maybe for a later note!

On the blog this week…

The blog this week -

A new episode of the Regulate Tech podcast - this one about the often fuzzy distinctions between open and closed.

A note on why the US returning to the endless frontier of science will be helpful (and should interest EU policy makers).

And, as usual, let me thank you for reading and sending comments and ideas — I appreciate them greatly. It is very helpful, and I learn from your ideas as well as criticism - so keep it coming!

Take care,

Nicklas